Remember the name: Kamil Kopúnek. For Italian fans the Slovakian can now take his place alongside Pak Doo-Ik and Ahn Jung-Hwan on the Azzurri’s podium of World Cup infamy. It may seem an unlikely trio, but all three players have in their time put paid to the Italy’s World Cup hopes, and in doing so represent the lowest points in the four-time winners’ otherwise impressive tournament record. But while defeats to North Korea in 1966 and South Korea in 2002 sent shockwaves reverberating around the football world, Italy’s lacklustre performance and ultimate capitulation in 2010 had a certain inevitability. After disappointing 1-1 draws against Paraguay and New Zealand, a win – while not essential – was certainly the Italian objective in their final group match against Slovakia. Instead, the Azzurri found themselves two goals down after 73 minutes, and despite rallying a late fight-back, Italy’s elimination was effectively sealed the moment late substitute Kopúnek burst between two defenders to lift the ball over Fabrizio Marchetti with his very first touch of the game. So low were expectations surrounding the defending champions’ campaign in South Africa that reaction to Slovakia’s third goal was less one of outrage and more a collective groan of relief and resignation.

Italy’s disastrous exit from the World Cup in 2010 made the euphoria of Italy’s victory in Berlin – still fresh in the memories of all Italians – suddenly seem every bit four years ago. In 2006, few would have predicted both finalists in Germany crashing out at the first hurdle in South Africa. And yet while the French can point to internal struggles and their federation’s misguided faith in an increasingly eccentric coach, whose bizarre alienation of fans, press, staff and players is reason enough for their shambolic demise, the Italians have fewer excuses. Certainly that was the view of fans, who on Italy’s return from South Africa, subjected their fallen heroes to a tirade of jeers and abuse as they trudged with hung heads through the arrivals gate at Rome’s Fiumicino airport.

To assess just how Italy went from World Champions to national disgrace requires a quick rewind to Berlin four years ago, when, just as in 1982, Italy’s national team emerged from the wreckage of domestic scandal as unlikely but worthy World Cup winners. The Italian coach Marcello Lippi had already decided not to renew his expiring contract with the FIGC (Federazione Italiana Giuoco Calcio), and three days after enjoying what he described as his “most satisfying moment as a coach”, was replaced by former Italian international Roberto Donadoni. It was a surprising choice: Donadoni’s greatest achievement as a coach so far had been to lead unfashionable Livorno to the top half of Serie A, and he certainly lacked experience at a major club. He was also faced the unenviable task of taking over a winning team in which any negative result is bound to be greeted with criticism. With the team still riding the highs of Berlin, Donadoni’s side’s performances were always going to compare unfavourably with Lippi’s, and the new coach struggled to assert his own identity on the world champions. It was a reign which seemed doomed from the start: Donadoni’s contract contained a clause stating it would only be renewed should Italy reach the semi-finals of Euro 2008 — when Italy were eliminated in a penalty shoot-out by Spain in the quarter-finals, everyone knew the game was up.

More surprising was what was to follow. The FIGC, in an unexpected move, recalled Lippi, who had spent the two years since the World Cup on the beach and at home in the Tuscan coastal town of Viareggio, basking in his new life as a national hero. Arriving at his first press conference since being recalled out of retirement, Lippi appeared tanned and relaxed, happy to once again don the federation blazer and “ready to pick up where [he] left off.” This statement of intent sent a twinge of discomfort down the spines of watching fans. The phrase “minestra riscaldata”, literally “reheated soup” is used in Italian soccer circles to describe the ill-conceived return of an ex-player or coach to his place of former glory, the idea being that it’s never as good second time around. Keen observers had to ask why Lippi, having achieved the sport’s ultimate accolade, would choose to give up a life of permanent hero-status to take Italy to another World Cup? The Azzurri’s victory in 2006 may have seemed unlikely at the outset, but even less probable was a repeat in 2010. Only Vittorio Pozzo, Italy’s coach in 1934 and 1938, had led a team to back-to-back successes, and not since Brazil in 1958 and 1962 had a nation won two World Cups on the bounce. Yet Lippi seemed happy to risk forever tarnishing his image of cigar-chomping hero of Berlin by attempting this extraordinary double.

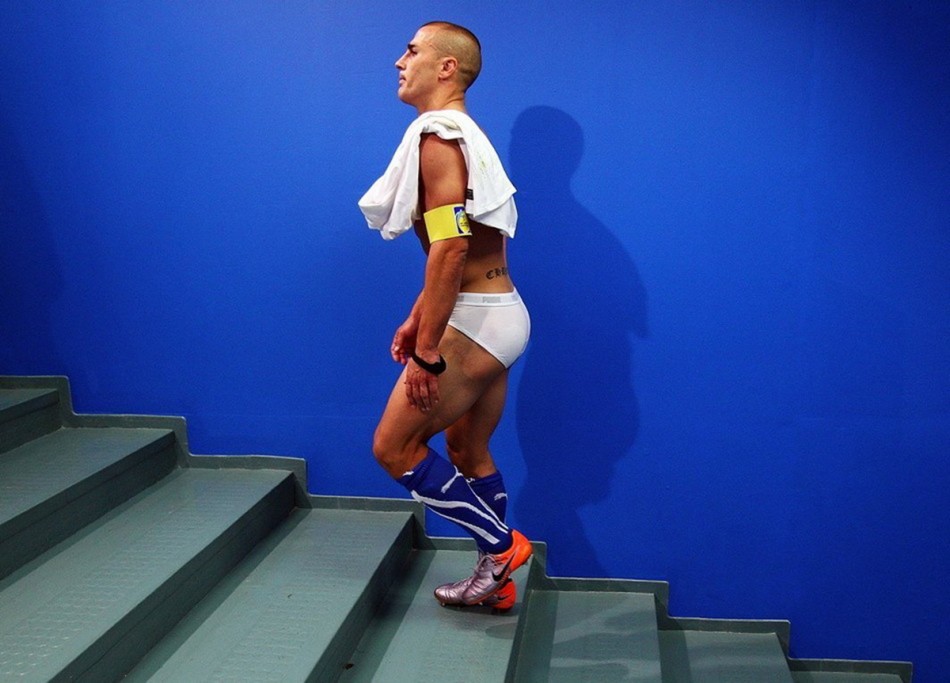

Italy’s World Cup-winning captain, Fabio Cannavaro, was guilty of a similar arrogance. Unlike former captain Paolo Maldini, (who retired from international football after the 2002 World Cup, only to watch his would-be teammates lift the trophy four years later), Cannavaro had won it all but still wanted more, just like Lippi. Majestic at the World Cup four years ago, his performances in Germany were enough to earn him the Ballon d’Or in 2006. A World Cup victory seemed like a natural moment to call it a day, yet Cannavaro continued to lead the Azzurri, despite showing inconsistent form since returning to Juventus from Real Madrid. Once one of Italy’s quickest defenders, Cannavaro’s rapid decline culminated, sadly, in being made to look every bit the 36-year-old in South Africa.

* * *

The defending champions qualified for South Africa relatively comfortably, yet Lippi’s dependence on the core group of players that had triumphed in 2006 spoke volumes about not just his short-term priorities but also his obsession with Italy’s World Cup win four years earlier. Many questioned the reliance on certain players from Juventus: given the Turin club’s poor season the inclusion of wayward stars Camoranesi, Iaquinta and the aforementioned Cannavaro this time around seemed to have more to do with Lippi’s strong ties to his former employers. Lippi’s coaching philosophy emphasises team spirit and unity, but while the heroes of Berlin still had a role to play, many had lost the form they’d showed four years ago, and – perhaps more importantly – all were four years older. Lippi’s responded to critics by reminding them of his World Cup pedigree, and to those who raised concerns over the age of the squad pointed out that its average age was actually younger than in 2006. But in Germany Lippi had struck upon a group of top professionals players at their peak, in 2010 the gulf between levels of experience was startling.

Perhaps in an attempt to silence doubters Lippi selected several younger players who shared just a few caps between them as late inclusions into the squad. All had enjoyed positive domestic seasons yet none had been used regularly during Italy’s qualifying campaign and all lacked international experience (the fact that most were plucked from Serie A’s smaller clubs meant they were unfamiliar with the kind of pressure reserved for top-of-the-table clashes or matches in the Champions League). Though their selection seemed a knee-jerk reaction by Lippi, some of these players were immediately thrown into the deep-end in South Africa. Genoa left-back Domenico Criscito and Fiorentina’s elegant playmaker Riccardo Montolivo acquitted themselves well in tough circumstances, but others, such as Juventus midfielder Claudio Marchisio and Cagliari goalkeeper Fabrizio Marchetti, appeared out of their depth. Montolivo and Marchetti only became first choices due to injuries to otherwise certain starters: Milan’s regista Andrea Pirlo damaged a calf just days before the tournament, while Gigi Buffon bowed out at half-time in Italy’s opening match after aggravating a problem with his sciatic nerve, an injury which ruled him out of the rest of the competition.

Though injuries to key men naturally proved a massive blow for Italy, the team was further hampered by Lippi’s disparate squad, which consisted of too many players unused to performing at this level. For a country with a long history of world-class playmakers, Italy went into this World Cup without an out-and-out number ten, a designated trequartista or fantasista in the Roberto Baggio mould. Without a player with such qualities, in all three of their matches Italy looked desperately short of creativity in the final third. At 35, Alessandro Del Piero was judged past his prime, while Francesco Totti’s protracted retirement from international football had effectively excluded him from rejoining the squad. Lippi’s stubbornness is perhaps most evident in his failure to call temperamental forwards Antonio Cassano and Mario Balotelli to the international fold. While Balotelli still shows regular signs of immaturity, Cassano has consistently impressed for Sampdoria over the last two seasons, helping the Genoese club to qualify for the Champions League for the first time in eighteen years. Yet Lippi continued to ignore him to the frustration of fans, often refusing to answer the press’s questions regarding the player’s exclusion.

The attitude of Italians — coaches, players, press, fans — before a World Cup is typically one of cautious optimism (or false pessimism). You may say Italians love a crisis: it takes the pressure off and makes an ultimately positive campaign all the more enjoyable. The national team is a notoriously slow starter in major tournaments, and most fans expect a rocky road to success. Yet this year Italy started poorly and only got worse, and there was a pervading sense of imminent failure prior to the defeat against Slovakia.

South Africa 2010 officially ranks as Italy’s worst ever World Cup performance. Just as in 1966 and 1974, the Azzurri failed to progress from the group stage, but this year they were unable to record a single victory in three matches — against Paraguay, New Zealand or Slovakia — finishing bottom of Group F. Following the disastrous elimination, it was Lippi who predictably received most of the blame. The coach even shouldered all responsibility in his post-match press conference.

Certainly Italy’s notorious press was quick to pounce. Alberto Cerruti, chief football correspondent of the Milan-based daily La Gazzetta dello Sport, described Italy’s performance as “unwatchable”, but seemed particularly disappointed with the casual manner in which Italy’s hard-earned title was relinquished. The director of Rome’s Corriere dello Sport, Alessandro Vocalelli, was more scathing, appearing on an online video just hours after the final whistle to bemoan Lippi’s “incomprehensible selections and inexplicable tactics” which had resulted in a “total, humiliating failure, from which nobody should be exculpated.” Yet others saw a greater issue with Italian football at large. Former Milan and Italy coach Arrigo Sacchi, himself no stranger to the scorn of critics, felt the root of the problem lay in Italy’s culture of “ignorance and violence”, citing a “crisis in the Italian system.”

* * *

Sacchi may be going too far by condemning contemporary Italian society, yet the state of the country’s game has been in decline for several years, to the extent in which it has become almost de rigeur to disparage Serie A, Italy’s domestic championship, once the most admired league in Europe. Sacchi pointed to the fact that Italian clubs crashed out prematurely in European competition last season. The one exception, Inter, have a foreign coach and an almost completely foreign squad. Indeed, of the twenty-three players Lippi took to South Africa, not one hailed from José Mourinho’s treble winners, the first time ever an Italian World Cup squad has not contained a single player from the nerazzurri. The conclusion one takes from this is that there is an excess of foreign players in Italy, whose presence denies promising Italian youngsters the chance of breaking through at the biggest clubs. Consequently, Italy’s 2010 squad included players from Genoa, Bari, Udinese and Cagliari, clubs hardly renowned for providing members of the Italian national team.

There are those in Italy that have suggested the return of a restriction on the number of foreign players a team may field at one time. But Italy is definitely not the only nation with a strong domestic league faced with this dilemma. England has also discovered that top-class foreigners may make for an entertaining league but their presence can be detrimental to the national team’s success. Spain – despite the plethora of foreign players in La Liga – seem to have solved this problem by selecting a squad mostly comprised of players from the two biggest clubs, Barcelona and Real Madrid. In contrast, German clubs work in closer conjunction with its federation, and their philosophy of investing in youth rather than spending heavily naturally encourages a strong national side.

FIGC president Giancarlo Abete has already announced an inquiry into Italian football’s “structural crisis”, but to suggest a shake-up of Italian system is excessive. The problems cited as causes of Italy’s poor displays in 2010 were already in place in 2006, when Italian football was also still reeling from the aftershocks of calciopoli. Some claimed it was this scandal which galvanized the team to victory in Germany, and Italian players certainly appeared lacking in motivation in South Africa. But Lippi was correct to blame himself: his return was gearing solely towards this event, and so he had no interest in making long-term plans and no vision of the future since it did not concern him. He was obsessed with the victory of 2006, and intent on repeating it all costs, at the expense of his own better judgment. Sadly for Italy, he did not have the means — either tactically or technically — to realize that dream. The FIGC showed desperate short-sightedness in rehiring Lippi, who in turn showed an alarming degree of footballing-masochism in attempting a second win in succession. For all Donadoni’s inexperience, had the Italian federation stuck by him Italy would have probably arrived in South Africa with a more balanced and settled side. Likewise the younger players who did not appear ready at this tournament would have no doubt been groomed specifically in preparation for the World Cup stage.

The effects of calciopoli have tempered spending in Italy, and over the last two seasons the biggest Italian clubs –Inter, Milan, Juventus, Roma, Fiorentina and Sampdoria — have put their faith in local young players who have grown into first-team regulars. Lippi’s replacement, 52-year-old Cesare Prandelli, has been selected by the FIGC specifically for his proven track-record with younger players. At Verona, Parma and Fiorentina specifically, Prandelli had built attack-minded teams around the promise of youth. Though he spent six seasons as a player at Juventus, Prandelli may benefit from having never coached one of Italy’s biggest clubs, and his lack of close connections to Italian football’s superpowers may work in his favour. Certainly he will employ a fresher, more open approach to player selection, already stating that Cassano and Balotelli will figure in his plans. More unexpected were his comments surrounding the sometimes controversial oriundi (naturalised citizens eligible for the national team) whom he declared “new Italians.”

While Italians may be Italy’s biggest fans, they’re also its harshest critics, and once the dust settles on Lippi’s second era in charge they’ll probably realise the future doesn’t appear quite so bleak. It would take a brave man to bet against Italy going far in Brazil in 2014. As this World Cup has already proven, four years can be an awfully long time in football.