“I WILL NOT TALK!” cries silent movie star George Valentin, as we fade in on his gaping mouth. Except his screams of anguish go unheard, both by his torturers and by two very separate cinema audiences: the one enjoying his latest Hollywood adventure and the one viewing The Artist, the new film by French director Michel Hazanavicius. Valentin’s words are only understood via a title card — a delightful joke that cleverly prepares audiences for cinema’s first commercial silent release in almost 85 years.

But how would twenty-first century movie fans react to such an audacious premise? The effect of hearing nothing but Ludovic Bource’s jaunty score is initially jarring. Though sound (or lack thereof) is not The Artist’s only technical departure from today’s type of movie-making. The film was shot using a 1.33:1 screen ratio common for the time, and at a slower 22 frames per second to achieve the slightly sped-up quality of the period (most movies today are filmed at 24fps). But the biggest surprise that comes from seeing The Artist in a packed theater (aside from the shock of how much noise cinema-goers actually make) is how quickly the audience settles into the unfamiliar.

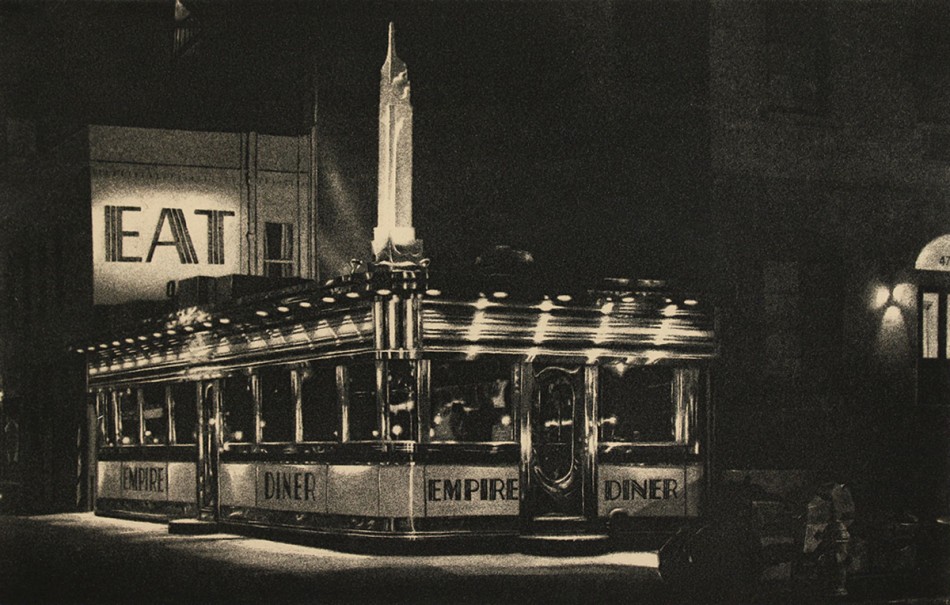

The year is 1927 (the same year The Jazz Singer was released) and Valentin, played by Jean Dujardin, is Hollywood’s barrel-chested action hero du jour, in spite of the fact that nobody has ever heard a word out of his mouth. Amidst the clamor surrounding this pencil-mustachioed matinee idol, a confident young flapper named Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) manages to breach the lax security of Kinograph Studios, talking (and dancing) her way onto his next feature. On screen, the two mismatched performers share a flirtatious scene, and off it, a brief but significant meeting in Valentin’s dressing room that will drive the plot forward.

Things are shaking up in Hollywood at large, too, with the advent of talking pictures. When burly studio boss Al Zimmer (John Goodman) reveals this revolution in sound technology to a skeptical Valentin, the proud star refuses any part, effectively signaling his own rapid professional and personal decline. With deft irony, the brand new medium catches the sprightly Miss Miller on the cusp of fame, propelling her from young aspirant to starlet in her own right. Caught in a frustrated marriage to a surly and disgruntled wife (Penelope Ann Miller), Valentin’s plight is aided by the presence of his abiding chauffeur/cook Clifton (James Cromwell), as well as his one-time on-screen companion, a faithful Jack Russell terrier that more than proves his worth to the washed-up actor away from the cameras.

It is a melodrama that has already been rehashed in Hollywood once too often, but never quite like this. As both protagonists grapple with their new-found circumstances, their feelings of guilt, longing and regret resonate twice as deeply due to the complete absence of dialogue. Consequently we are forced to infer everything from each nuanced smile, stolen glance and wiped tear. A nostalgic fascination for the forgotten era notwithstanding, The Artist packs the purest emotional punch I’ve felt at the movies in a long time.

Though cinematographer Guillaume Schiffmanit shot the film in color, every frame positively shines with all the white splendor of the pre-war Los Angeles sun (before the smog set in). Every detail is recreated with unnerving accuracy. It is rare to see a period movie suggest another epoch with such meticulousness, and I repeatedly lapsed into forgetting the film was brand new. Yet the film’s extraordinary technical research would have been for nothing without the winning performances of its two leads, the dashing and handsome Dujardin — who had previously starred in Hazanavicius’ series of spy spoofs, OSS 117 — and his female foil, the dazzling Argentine-born Bejo (daughter of filmmaker Miguel Bejo and Hazanavicius’ wife). Both possess the kind of expressive faces that belong to another time, before movie stars became CGI facsimiles of each other. Would any of today’s A-listers abandon their ego enough to perform without speaking? Here the film’s principal device enables its ultimate success, which hinges on the fact that neither actor is recognizable to audiences outside France. The tale is all the more absorbing precisely for the fact that we do not know the sounds of their voices.

For the first ten minutes I found myself wondering how long this central gimmick could be maintained, while at the same time hoping that the filmmakers would have the guts not to abandon the “novelty” mid-way through. I was reminded of Pleasantville (1998), another clever film that used technical device to tell a story, allowing color to subtly infiltrate a black-and-white fifties suburbia. I expected a similar turning point during The Artist, but instead the movie itself plays on its audience’s inevitable questioning — we are repeatedly invited to second-guess the ingenious conceit only for the filmmakers to consistently have the last laugh.

Nominated for six Golden Globes, twelve Baftas and ten Academy Awards, The Artist arrives under a weight of expectation and is not without flaw. The ending feels hurried, while the score — in a supposed nod to an altogether different movie era — borrows from Hitchcock’s Vertigo, a curious decision that apparently provoked the ire of that movie’s leading lady, Kim Novak.

Just as Woody Allen’s recent Midnight In Paris implored against the perils of nostalgia, so The Artist — while clearly celebrating the bygone age it so effortlessly evokes — is more keen to address the present. The film is no doubt a subtle critique of Hollywood’s current cinema, but more importantly a timely allegory for the problems of the modern world. “Make way for the young!” Miller exclaims enthusiastically to a reporter in one scene, in a manner reminiscent of twenty-first century society’s at times all-embracing attitude to new technology. George Valentin is a man overwhelmed by the detrimental effect of our alarming advancement, that is the elimination of what went before. He risks being phased out, along with his job and industry as he knows it, a highly relevant phenomenon of which our current economic climate is a direct consequence. What lingers after seeing the The Artist is the affirmation that only by appreciating the past can we begin to fathom the present.