When I was a boy my best friend was another boy named Joe. We must have met when we were about four or five, and from that point on spent what seemed like most weekends together. Thanks to this near inseparable friendship, Joe’s parents quickly became close friends with mine. Both were artists — his father a sculptor and his mother a ceramicist — and both were pretty successful in their respective fields. My family and his would often go to the cinema or have dinner together at the weekends, and then one of us would sleep over at the other’s house (Joe and I had met before my brother Alex was born, but once he was old enough to walk the two of us became three). Joe and his parents lived in a large house on the corner of a main road. It had three floors and a separate building that acted as his mum’s workshop, as well as a spacious garden, where Joe and I spent whole days doing what probably amounted to nothing much. In the far corner of the garden underneath a giant pear tree was a two story construction made of scaffolding and planks of wood, from the top of which we could see over the fence and into the street. One day we rested a piece of drain pipe across the scaffolding and the fence and poured water onto unsuspecting passers-by. When one particularly irked middle-aged gentleman asked us what we thought we were doing Joe told him we were watering the pavement. On another occasion we spent an afternoon tossing over-ripened pears into the street, which was fun until the police knocked on the door.

Perhaps in an effort to avoid further run-ins with the law, Joe’s dad used the same scaffolding and wood planks to construct a life-size biplane on the lawn. From his workshop down in the basement he’d fashion toy swords for us out of wood. On another occasion he crafted us a pair of walkie-talkies, equipped with a plastic wire aerial and a knob that turned. It’s hard to imagine what kind of fun could be derived from what were essentially two wooden blocks painted black, but somehow Joe and I managed to keep ourselves suitably entertained for hours on end. Joe’s dad had travelled across the western United States, bringing home with him a number of interesting Native American artifacts that adorned Joe’s bedroom. He even had a wigwam out on the lawn that we never dared sleep in overnight. I don’t know how many days and nights I spent in that house but I can still recall every last detail, right down to the pale green sponge-like texture of the upholstery on the sofa and the paisley pattern engraved into the handles of the family’s cutlery.

When I was about ten, Joe’s parents sold their house and moved to another town, some forty minutes away. The new house was much smaller, but with the money they made on the sale they were able to buy a rustic property in the northernmost corner of Tuscany. Joe’s dad wanted to have access to the stone from nearby Carrara, a town known throughout the world for its marble. I remember them going there that summer to work on the house (which from the photographs I’d seen needed some attention). We’d already begun spending long vacations in Italy, and the following year we jumped at the chance to spend a week or two with them, and did so every summer for the next five years.

While the house itself was located in an area of Tuscany called il Lunigiana, in the province of Massa, it was only a short distance across the Ligurian border to La Spezia. Consequently the local license plates seemed to be evenly split between MS and SP. Exiting the A15 Autostrada at Aulla, it was a short drive to a small town called Serricciolo. From there we drove up a winding hillside road to the tiny hamlet of Verpiana, where we turned left around a large brick barn and into the dusty courtyard. The area was dotted with semi-abandoned pieces of farming equipment, hens clucked across the hay and cobblestones and a cat slept underneath the wheels of an already-vintage Fiat. The house was on the first floor: beneath it were three ancient arches under which Joe’s parents’ Citroën was parked. To get up there you had to walk up a semi-covered stone staircase with a wobbly metal handrail, which brought you out onto a spacious terrace. The house itself was extremely roomy with several bedrooms, some of which you could only get to via the terrace. The other details were as one would expect: terracotta floors, whitewashed walls, painted wooden shutters and iffy wiring.

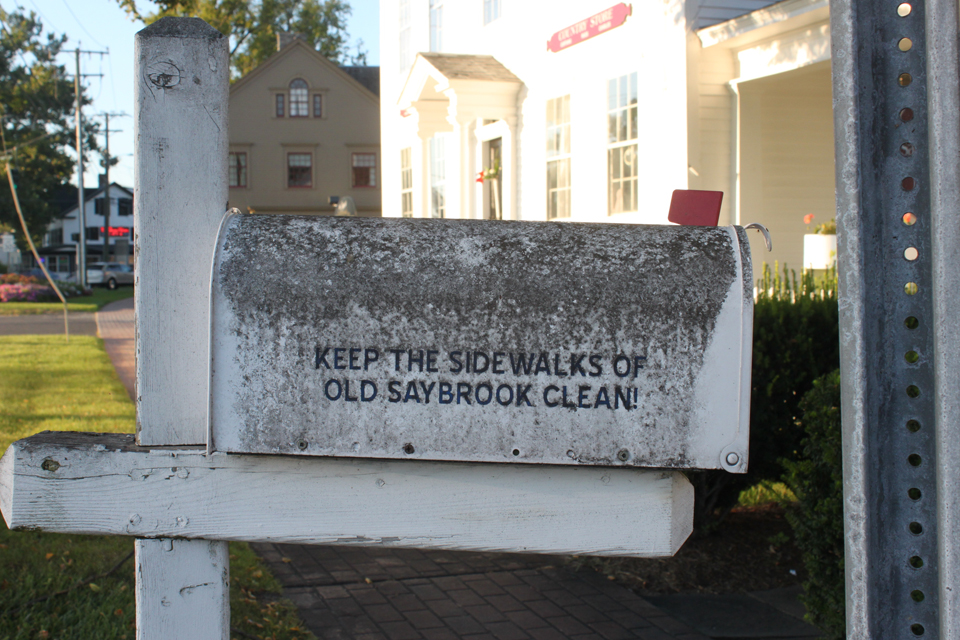

Beneath the house was a maze of cellars and rooms that had clearly not been inhabited in decades, if not centuries. I remember one day Joe and I entered a secret door behind the archways where we’d parked the cars. If we’d explored further we’d have probably walked in on someone having lunch, as it seemed every home in the village was connected, as if buildings had sprung organically from that central point. A long white tunnel — more in the style of the Amalfi coast or a Greek island — extended out of the courtyard and lead to another road. Inside there were several other homes. Occasionally we’d run into other kids, who our attempts to befriend weren’t met with much success. They were quite unlike the other young Italians I’d met. At the other end of the tunnel was an alimentari, a small convenience store, the kind of place you enter through a beaded curtain and where the owner is a woman in slippers. It was a handy enough place to pick up milk or a box of pasta, but for a real supermarket we had to drive down to the next town, Serricciolo.

* * *

Serricciolo also had a bar next to the railway tracks, where we’d often stop for a morning coffee or post-beach refreshment. Joe and I often spent our time playing a football video game that ran on 20 lire coins. In addition to the aforementioned Sidis supermarket, Serricciolo also boasted a florist, a newspaper kiosk, a wedding dress shop, and a hardware store that also sold nice things for the home. Yet Serricciolo’s most important contribution to its range of local amenities was its pizzeria. The place was everything you want in a pizzeria and nothing more: plastic tablecloths, no atmosphere to speak of, and a pyramid of chocolate-covered profiteroles rotating behind the door of a glass fridge. The pizza was so thin it was almost transparent and its circumference so huge that I don’t know why they even bothered putting it on a plate. Always a purist when it comes to pizza I never veered from the margherita. The mozzarella would rapidly melt into the tomato creating a delicious sauce the colour of sunburn. I’d devour the whole thing in about ten minutes.

Sometimes after dinner we’d drive past the pizzeria to Fivizzano. This pretty hilltop town was also damaged during the war and is prone to earthquakes, but its main square, Piazza Medicea, has remained intact. There we’d order un gelato from the bar and eat it by the fountain (commissioned by Cosimo III de’ Medici), distinctive for its numerous carved fish from whose mouths spring jets of water. I loved the energy of those summer nights and the fact that families would be out together after midnight, kids running around in the dark, illuminated only by buzzing fluorescent lampposts.

On the way to Fivizzano was there was a nearby swimming pool, with a great water chute and high diving boards. It was kept in the shade by a forest of pine trees, and I remember one day a bee managed to sing me underneath my watch. Alex’s thick mop of blond hair (a “thatch” as my mum used to call it) meant he always drew attention from Italians. This was especially true at the swimming pool, where he’d quickly impress local teenagers by showing no hesitation in leaping into the water from the highest diving board.

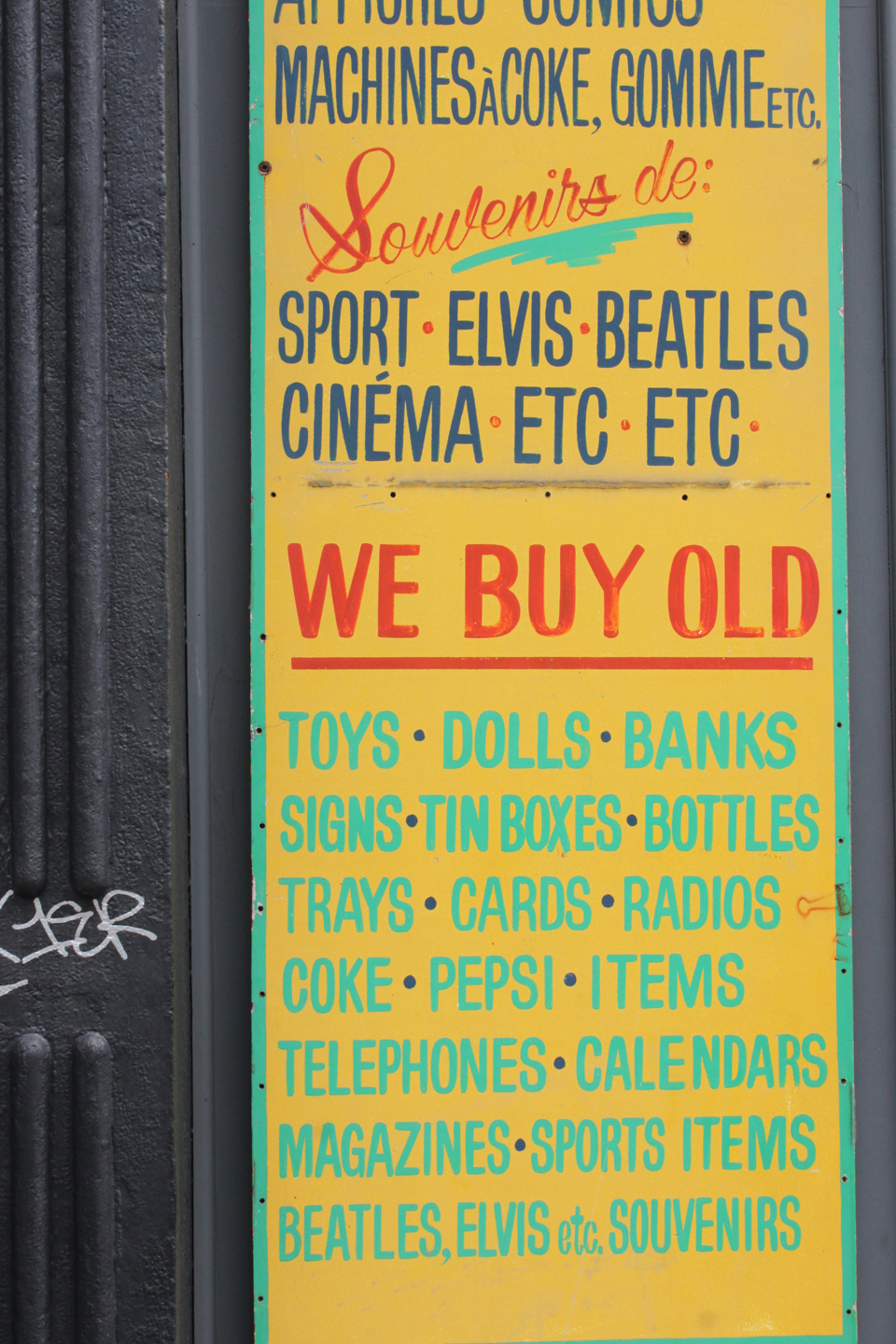

After Serricciolo was Aulla, a mid-sized market town whose old centre was destroyed by Anglo-American bombings in 1943. The modern town that had sprung up in its place was a lot of concrete and marble, and decidedly unpretty. Aulla hosted a bustling market which we’d go to browse and pick up cheap frying pans, flip-flops or unofficial football merchandise. Meanwhile there were the usual shops: Benetton, Stefanel, plus a somewhat no frills sports store, where I bought my Milan 1990-91 shirt. I also have a photograph of myself standing outside the shop next to a life-size cardboard cutout of Franco Baresi. One day we noticed giant posters of football players (Baggio, Gullit, etc.) on display in the supermarket. The cashier explained they could be ours if we saved the wrappers from 12-pack boxes of Kinder Brioche. So for several days, Joe, Alex and me ate more of these apricot jam-filled breakfast cakes than was possibly healthy, but it was enough to earn us a poster each. (Mine, of a 22-year-old Paolo Maldini, still hangs on the wall of my apartment.)

When we weren’t visiting other towns or picking up provisions, we’d invariably spend the day by the sea. A place I loved to visit was Portovenere, a busy fishing town built into the cliffs and best reached by boat from the elegant port of Lerici. There was no beach, just a long cluster of boulders, with steps down to the water. When a boat sped across the bay the water would bounce up against the rocks. Joe and I used to snorkel around the tied-up rowing boats, trying in vain to catch darting minnows with our hands. We also collected broken fragments of old ceramic pots, which we took home and used to make a mosaic on the floor of the house. In the late afternoon we’d walk up to the gothic church of San Pietro, which offered spectacular breezy views of the Mediterranean. My dad used to always point out the grotto named after Lord Byron and tell us the story of how the poet swam across the bay to see Shelley in Lerici, and that Shelley later died in a boating accident just off the same stretch of coast.

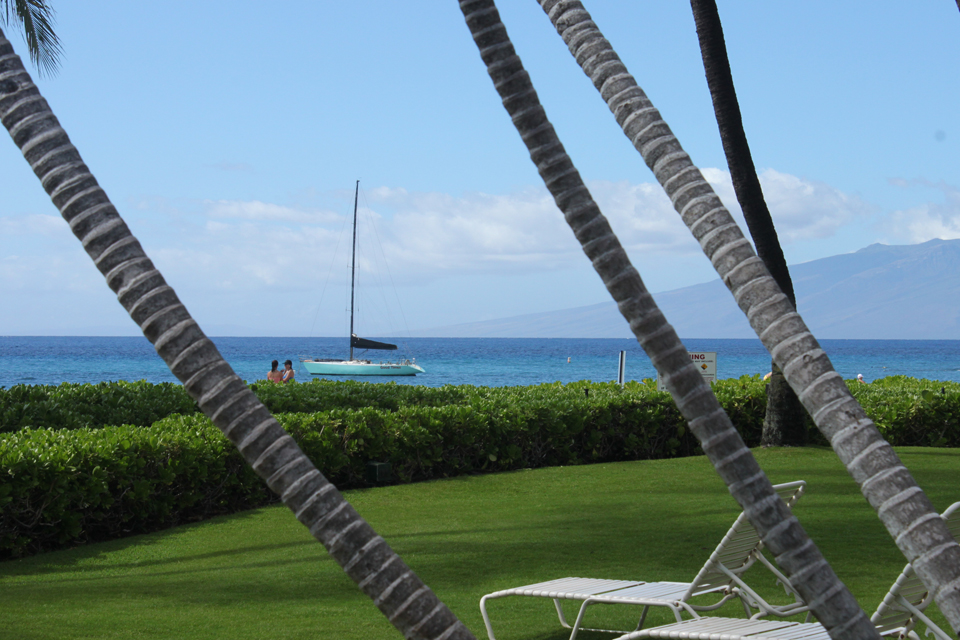

There were beaches at Sarzana and San Terenzo but they were a little cramped, and so usually we drove to Marinella. We’d park opposite an Agip station on a road lined with pine trees, and spend the rest of the day there, sometimes until dusk. Unlike Liguria’s rocky coastline, Marinella was a classic Italian beach, packed with multi-generation families gathered under umbrellas and ragazzi spending the afternoon sunbathing or playing volleyball. I’d often run and get ice cream or bomboloni con crema from a little hut. We’d usually pack our own sandwiches, after which I used to begin to doze off on my towel. Through my dreamy state I’d hear the voice of the man carrying a large icebox filled with coconut. “Cocco! Cocco bello!” it would sing, more loudly as it got closer, before drifting away again, getting lost amid the soothing murmur of unintelligible chatter and gently breaking waves.

* * *

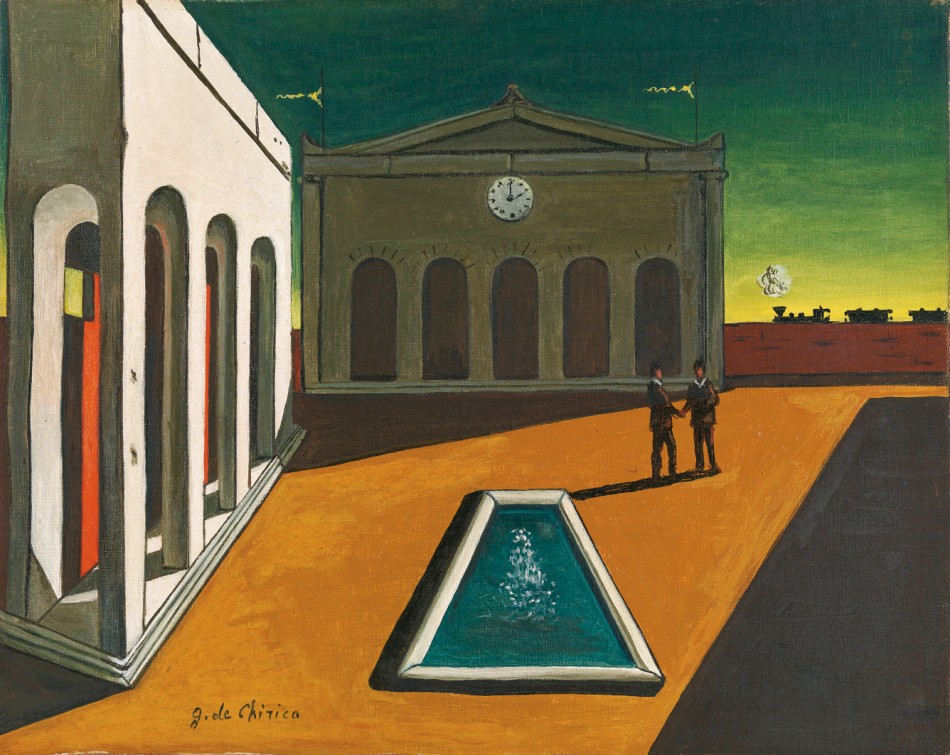

Life at Verpiana revolved around the terrace. Joe’s parents had furnished it with several pot plants and safari chairs and fold-up wooden chairs. There was a large table — or rather, a table top and two trestles — to eat at. It was too hot to eat lunch outside but when the sun had shifted the terrace became a lovely place to sit before dinner. Across the courtyard and beyond a neighbour’s clothesline was visible a spectacular mountain range that would turn pink each evening as the sun departed. I often wanted to believe that the central peak was the mountain featured in the logo of Paramount Pictures. (Years later the mountain I was thinking of was pointed out to me in Piedmont.) In the evening we’d hang our beach towels over the wall to dry and play football with one of those mini plastic balls they sell on the beach (one of the goals was the spindly railing at the top of the stairs, which meant every time a shot went in that direction someone would have to chase down after the ball and retrieve it before it bounced into an old cellar or punctured beneath a rusty tractor). On rare afternoons when Verpiana suffered a brief yet biblical rainstorm I’d hole up indoors and spend an afternoon reading or drawing. There was no television and the only place to listen to music was in the car, so we’d instead engage in epic ping-pong or Subbuteo tournaments, for which I remember creating paper advertising hoardings out of Brooklyn chewing gum wrappers.

I always looked forward to the evenings. I still remember what a blissful feeling it was to be standing in the kitchen under the bright glow of a single light bulb, watching the pasta fall into a vast pot of boiling water. Fresh out of the shower, tanned from the beach, a clean t-shirt and starving from having not eaten since lunchtime, the anticipation of another fun dinner out on the terrace was blissful. Though there were a couple of outside lights, the table was decked with ceramic candle-holders crafted by Joe’s mum, between which Joe and I would try to build wax bridges as the candles burnt down through the course of the evening. In the total silence of midnight we’d be able to spot bats circling around the barn and constellations directly over our heads, which is when my dad would start saying slightly ominous things like, “They’d never find me here.”

One of the neighbours was an elderly war veteran named Guido. He always said hello and sometimes he’d bring us a bottle of his own wine that was probably best described as “rustic”. My dad spoke better Italian than any of us and sometimes chatted with the old man over a cigarette. When my dad told him the route we’d taken to get here Guido opened his eyes with a hint of recognition. “Ah yes, Germany,” he said, as if summoning some vague recollection. “They eat a lot of potatoes there, don’t they?”

I sometimes wondered what Guido and his wife — a typical rural home-keeper who never took off her apron — used to make of us. I’m sure they were utterly baffled why a bunch of foreigners would want to spend summer in a part of Italy that no Italian would ever have reason to visit. Even at a young age, there was something quite embarrassing about it all. In between my fun I felt uneasy being in Verpiana for two sunny weeks when everyone around us had to spend all year there, year after year, and probably hadn’t been anywhere else in a long time. This feeling was exacerbated by Joe’s parents’ other guests, whose visits sometimes overlapped with ours. As nice people as they obviously were, their presence made the house feel like a ready-made facility for middle-class Brits to live some idealized version of a rustic Tuscan lifestyle. Nowhere could have been further removed from Italy’s celebrated tourist destinations. Verpiana, Serricciolo and Aulla were unknown, unfashionable places where real people lived, but have as much to do with my love of Italy as Rome or Venice or Florence.

Our relationship with Joe and his family ended abruptly, the reasons for which I won’t go into here as many details are still unclear to me. I haven’t seen Joe since Christmas 1994, but I understand he’s now married with a young son. His dad died a few years ago, but his mum is still working and as far as I know still visits the house in Verpiana. About six years ago, when I was living in Italy, my girlfriend (now wife) began taking singing lessons from a retired opera singer in Carrara. One Saturday in early summer I went with her on the train from Florence. While she had her lesson I strolled around the town. I had been once before, and remembered how the marble had turned the river water white. It was a warm day, so after lunch we took the bus down to Marinella. We walked past the pine trees, took off our shoes and stepped onto the sand. Many years had past and we were at the opposite end of the beach, but the view of the hills looked the same from any distance. Staring down the coastline I could just make out the yellow sign of the Agip station several hundred metres away, peeking through the haze like a mirage. Then, through the hypnotic sound of the sea I heard his voice, faintly at first, but getting louder: “Cocco! Cocco bello!”. As soon as it had sung, the voice started to fade away once more. And then, it was gone.

A version of this article, translated into Italian by Elisa Sottana, is on the site of Rivista Inutile.