Where were you ten years ago tonight? I was at San Siro.

“Luci a San Siro di quella sera

che c’è di strano siamo stati tutti là

ricordi il gioco dentro la nebbia

tu ti nascondi e se ti trovo ti amo là”

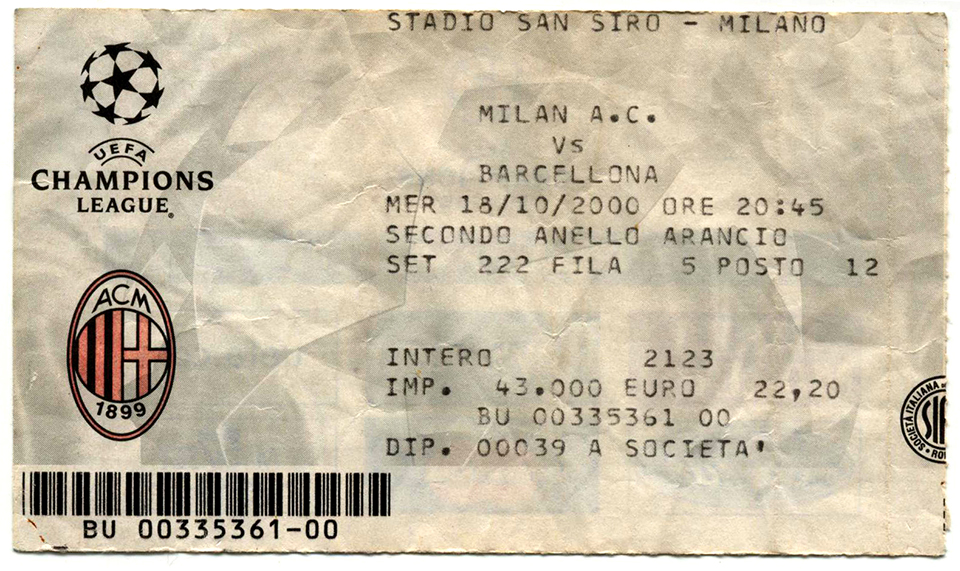

There’s a very special moment when you enter one of the world’s great football stadia for the first time. You’ve not even begun to look for your seat yet; you’re pacing around the external perimeter looking to match the apparently random series of numbers stenciled onto concrete to those printed on your ticket. Fans hurry past you in the opposite direction and you begin to move more briskly because you fear kick-off is approaching when, through a break in the concrete, you catch a glimpse of what awaits on the inside. The crowd, the grass, the noise. I still remember that moment at Milan’s Stadio Giuseppe Meazza, better known as San Siro, where, having undergone a routine frisking by the carabinieri, I climbed up the stadium’s vast swirling ramps and spiralled staircases to reach the second tier. Finally locating my section, I stepped out into the blinding glare of the floodlit arena just as the away team was being announced. I looked up and saw the smiling face of Barcelona full-back Sergi being projected from the scoreboard, a beaming mug-shot that provoked nothing but a cacophony of furious whistles from the 80,000 home fans. I gathered my bearings and found my seat. I’d seen innumerable matches at San Siro from the comfort of my living room, and one hot day in August as a fourteen-year-old I’d even implored my dad to take a detour off Milan’s tangenziale, just to spend ten minutes wandering the dusty car park of the deserted stadium. But none of that prepared me for my first experience inside this storied venue which was, and remains, indescribable.

Television does not convey even half of what goes on inside the stadium. San Siro is built with steep tiers that put you on top of the action, and every tackle or attacking move is met with deafening roars of furious disapproval or wild applause. Despite the undoubted glamour of the fixture — Milan vs. Barcelona in the Champions League — I remember little about the match itself, which finished 3-3 (Rivaldo scored a hat-trick and Albertini hit two memorable goals from outside the box). For the bulk of the ninety minutes I was mesmerized by the Curva Sud, where Milan’s strongest supporters’ groups, the Fossa dei Leoni (Lion’s Den) and Brigate Rossonere (Red-and-Black Brigade), congregate. Gigantic flags were unfurled and waved at intervals, huge drums were pounded throughout the match, and goals were celebrated with unruly pink flares. Throughout the evening my gaze became fixated on the top of the curva, where on a plexiglass partition separating the second and third tiers sat a row of a hundred, maybe two hundred pairs of denim-clad legs belonging to calcio-obsessed ragazzi like myself. I went to bed that night with the noise of the crowd still ringing in my ears, unable to quite comprehend where I’d just spent the evening.

I was twenty-one, and studying for a year in the university town of Pavia, just south of Milan. It didn’t take me long to lose interest in the routinely shambolic Italian higher education system, and I instead began devoting as much time as possible to more pressing cultural opportunities, namely learning Italian and watching calcio. The first of these goals was achieved with minimum effort, as my roommate, a devout milanista named Federico, and I, hit it off immediately. The second required little work on my part either, as Pavia was just a thirty-minute train journey away from Milano Centrale, from where San Siro was a simple ride away aboard Milan’s basic metropolitana.

To my surprise tickets for games at San Siro were easy to obtain, and considerably cheaper than those for matches in the Premier League. I bought a season ticket for the second group stage of the Champions League for 90,000 lire, roughly the cost of a single ticket for a pre-season friendly at Leicester City. I had discovered that Milan tickets could be purchased at my local branch of the Cariplo bank, one of Milan’s sponsors. So as soon as tickets were made available (often less than a week before the match), I dutifully waited in line with local pavesi women in fur coats looking to pay a bill or collect their pension. At the counter I was met with a bleary-eyed cashier, who removed the cigarette from his mouth just long enough to ask me if I had a seating preference. I felt I must be inconveniencing the poor banker who’d been lumbered with the additional task of dispensing football tickets, and I was always amused by how, with a quick tap on the keyboard, his monitor switched from a checking account to a colourful San Siro seating chart.

Considering I wasn’t an account holder, over the next few months I found myself visiting that bank fairly frequently, and I was soon able to tell the cashier precisely where I wished to be seated: secondo anello rosso, preferably right of centre, which was closer to the Curva Sud but still central enough to watch the game closely. I became drawn to San Siro in a way that even drew bewilderment from my football-loving Italian friends. I remember a group of ragazzi looking at me incredulously one cold wet night in January, when I declined their offer of dinner in favour of Milan’s Coppa Italia semi-final with Fiorentina.

I made a habit of seeing Milan more than Inter, primarily because I’d always been simpatizzante towards the rossoneri since I’d fallen in love with calcio a decade earlier. The team coached by Sacchi and Capello had dominated Italian and European football in the late-eighties and early-nineties, and I’d grown up watching Baresi & Co. carving victories out of the Milanese fog. Plus Federico was milanista, and he’d have probably thrown me out had he found out I’d paid to watch Inter. Of course, thanks to my ties to Florence my real team was Fiorentina, who I saw beat Milan 2-1 at San Siro. Against Inter, I wore my Viola scarf defiantly, trying to ignore the stares of the several thousand nerazzurri fans that surrounded me. Perhaps fortunately for me, Fiorentina were hammered 4-2. Away from the bright lights of the stadium it was a different story, and I always removed my scarf or anything that would signal my allegiance before returning to the station around midnight.

* * *

It was a far from vintage season for either Milanese club. Milan had slid out of the Champions League at the second group stage after drawing three home games with Galatasary, Paris Saint-Germain and Deportivo La Coruna, thus ending their hopes of disputing that year’s final at San Siro. Despite some impressive earlier results — including a 2-0 victory over Barcelona at Camp Nou and a convincing 3-2 league win over eventual scudetto winners Roma — this was the final straw for Milan president Silvio Berlusconi, who’d never truly warmed to Zaccheroni nor his insistence on a three-man defence. “Zac” was replaced in March by former Milan captain Cesare Maldini (Paolo’s dad), who immediately reintroduced a 4-4-2 system.

Inter’s season had been thrown into jeopardy as early as August, when they suffered a humiliating exit from the preliminary round of the Champions League at the hands of Swedish minnows Helsingborg. A 1-0 defeat at Reggina on Serie A’s opening day led to Marcello Lippi’s resignation; 1982 World Cup hero Marco Tardelli took over the reigns of what would prove to be one of Inter’s darkest seasons in living memory. Having been relegated to the UEFA Cup, the team was knocked out of that competition too by unfashionable Spanish outfit Alaves, after which fans demonstrated their disapproval by burning stadium seats and launching a makeshift incendiary device at the Inter team bus. Domestic results hadn’t helped matters: the entire Curva Nord boycotted the first half of a league match with Atalanta, returning in the second half with a banner that read “Sorry we’re late: did we miss anything?” The afternoon concluded in infamy when a group of Inter fans hurled a motor scooter from the second tier of the stadium onto seats below.

Consequently, by the time the second Milanese derby of the season came around, both sides were effectively out of the title race. In truth, neither side had ever really looked like challenging for the championship. Roma had led the way since the autumn, with Juventus and Lazio in closest pursuit. Although both Milanese clubs were still looking to secure a place in the following season’s Champions League, unusually this derby would not have a direct bearing on the outcome of the scudetto. Yet so much of Italy’s media is based in Milan that the match was still awarded the usual high dosage of hype and hyperbole.

The Milanese derby is known locally as Il Derby della Madonnina, after the little gold Madonna that sits atop the main spire of the city’s Duomo. Due to the upcoming general election on Sunday, unusually the match had been brought forward to a Friday night, and weekend optimism bounced through the sunny May evening as I stepped off the train just in time for aperitivo. It was still light when I strolled from the Lotto metro stop to San Siro. Inside, the stadium was bulging. Clearly more tickets had been sold than actually existed, as myself and a pair of teenage girls wearing Inter scarves found ourselves sharing two seats between the three of us in the front row of the second tier. At my feet a Milan fan lay horizontally so as not to obscure our view, his head propped up by his elbow as if watching television on the living room rug.

Milan and Inter fans are renowned for their generally amicable coexistence, though the derby is always a little different, and the usual deafening atmosphere inside San Siro was spiced with a unique sense of anticipation unlike any I’d experienced during previous visits. The stadium choreography for which Italian fans are known takes months of preparation in secrecy, and Milan and Inter ultràs go to extraordinary lengths to out-do each other in what is an integral part of the pre-derby show. Each curva reveals its efforts shortly before the teams take the field, inciting fans and lending the game further sense of occasion. Milan began by unveiling the giant head of a salivating devil which spanned the height of the second tier, while fans either side held up red and black paper to make a checkerboard effect. Fans cheered and applauded. Inter responded with a gigantic version of its logo and club symbol, il biscione, the snake. Underneath a banner read: “F.C. INTER: ETERNO AMORE”. More polite applause. But Milan’s fans weren’t quite finished. As Inter’s applause faded they unfurled an extra banner off the edge of the tier, in which the hands of the devil were seen to choke the life out of Inter’s snake. Cheers and laughter filled the stadium. 1-0 to Milan, and the teams hadn’t even kicked-off yet.

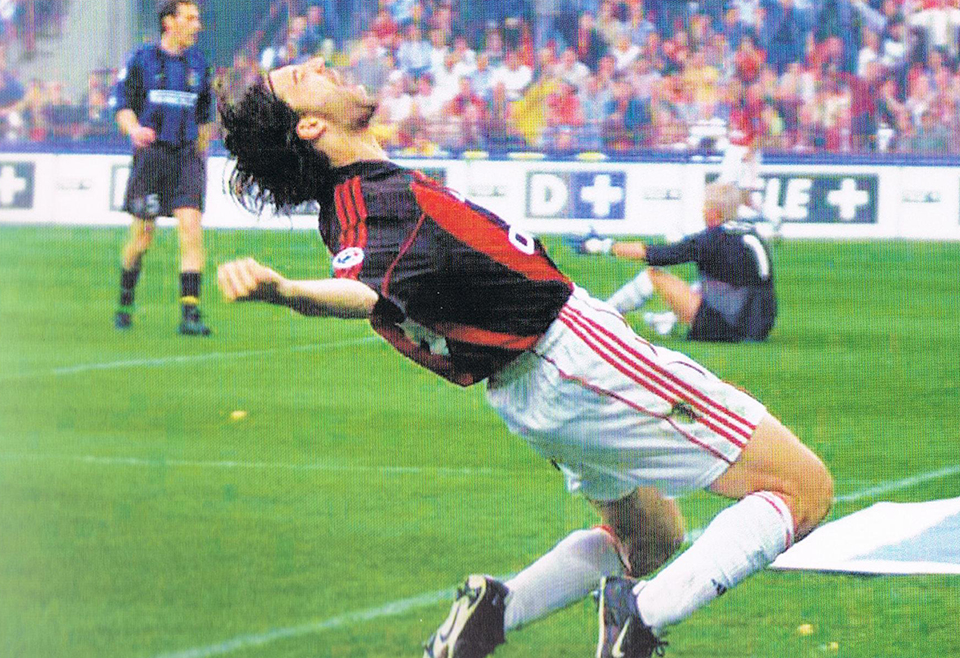

The pre-match formalities out of the way, all that remained was the game itself, and suddenly I remembered why I was here. Perhaps ceding to fan pressure, coach Maldini had dropped the out-of-favour German striker Oliver Bierhoff, instead partnering Andriy Shevchenko with Gianni Comandini. The young Italian forward had made only a handful of appearances so far, so it appeared unlikely that he should be thrown into the mix in such an important match. But before anyone could begin to question the decision Comandini was already on the scoresheet, having latched on to Serginho’s defence-splitting pass to slide the ball past Inter goalkeeper Sebastien Frey with just two minutes and forty seconds on the clock. The early goal settled Milan, and Inter struggled to react. Shortly afterwards, Serginho found space again on the left wing. The Brazilian winger’s inviting cross was met at the near post by Comandini who doubled his tally and Milan’s lead. Less than twenty minutes had passed and Maldini’s gamble looked to be already paying off.

Derby matches are historically tight affairs, so it in some ways a surprise when Milan added a third goal shortly after half-time. Federico Giunti, starting only due to Albertini’s absence, curled in a dangerous free-kick from the right. Neither attackers nor defenders got a head to the ball and it bounced once in front of Frey, wrong-footing the keeper and landing in the unguarded net. Giunti correctly claimed the goal, the nature and the circumstances of which immediately reminded me of another match on which Milan had imposed a total domination. In the 1994 European Cup final against a strongly-fancied Barcelona, the rossoneri had raced into a two-goal lead through Daniele Massaro, before Dejan Savicevic had scored his side’s third goal with a deft lob from a similar position to Giunti’s on the right wing, effectively ending the contest. Milan ended up 4-0 victors that night in Athens. Where would the scoreline end tonight?

The fourth goal wasn’t long in coming. Once again Serginho showed his pace down the left flank, beating Matteo Ferrari to the ball by leaping to swing in a cross with both feet, as if his legs were bound together like those of a table football player. At the far post, Shevchenko got his head first to the ball to put the result beyond any lingering doubt. By now Inter fans had begun to leave the stadium in droves, their home derby having turned into a festa milanista. “Siam’ venuti fin qua, siam’ venuti fin qua, per vedere segnare Sheva!” (“We’ve come here to see Sheva score”) sang the rossoneri faithful, to the tune of Scott Joplin’s “The Entertainer”. It was all too much for one overly sensitive Inter supporter, who ran onto the pitch and attempted to altercate with Alessandro Costacurta as he prepared to take a free-kick. Milan’s veteran defender barely reacted, and the fan was escorted swiftyly from the playing field to a chorus of whistles and derision.

For Inter’s shell-shocked players the final whistle couldn’t come soon enough. Television cameras next to the Inter bench caught Tardelli mouthing “Mamma mia…” while looking to the heavens. Yet again the club’s summer spending had failed to generate results. Ronaldo had missed the entire season through a second injury to his patellar ligament, and despite a potent strikeforce comprised of Christian Vieri and Alvaro Recoba, a supporting cast of newcomers such as Farinos, Dalmat and Gresko had failed to have the desired impact. Milan took full advantage. The Georgian defender Kakha Kaladze had slotted instantly into the side since arriving from Dynamo Kiev during the January transfer window. It was Kaladze who made Milan’s fifth goal, drilling in a low cross from the left which Shevchenko pounced on before the oncoming Frey.

San Siro was now quite literally rocking, and I felt the concrete stands vibrating under my feet. Few Inter fans probably saw the sixth goal, their numbers having begun to dwindle rapidly around the hour mark. Milanisti meanwhile had begun to cheer every pass, leaping on the terraces, their arms locked in unison, enjoying chants of “Chi non salta nerazzurra è, è!” (“Whoever’s not jumping is an Inter fan”). There was a pause in their celebrations just long enough to witness man of the match Serginho burst through Inter’s tired back line and end the rout. Six-nil, sei a zero.

* * *

MILAN 6 STREPITOSA! screamed the front page of Saturday’s Gazzetta (the number six, or “sei”, is also Italian for “you are”). It was Milan’s first derby win in the league since November 1993 (although they had beaten Inter 5-0 in a Coppa Italia fixture in January 1998). The result sealed Inter’s miserable season and allowed Milan to end their season on an unforgettable high-note. Ironically, Inter actually finished two points ahead of Milan in Serie A, yet both teams failed to qualify for the following season’s Champions League. Not even Silvio Berlusconi’s election victory over Francesco Rutelli (a Lazio fan) two days later could divert attention away from the biggest story of the weekend.

Inter struggled to recover: thumped 4-2 in the next derby, they lost the 2001-02 scudetto on the last day of the season with a shattering defeat at Lazio. The inerazzurri were further frustrated by consecutive Champions League exits in 2003 and 2005 against a Milan side that now included Dario Simic, Andrea Pirlo and Clarence Seedorf, all three of whom had been sold to their city rivals. Inter’s fortunes were resurrected in the wake of calciopoli, the team winning four consecutive titles and racking up a 4-0 derby win in 2009. Milan won the Champions League under Carlo Ancelotti in 2003 and 2007, a trophy which continued to elude Inter until Jose Mourinho led the club to a treble success in 2010.

But the night of May 11, 2001 is hard to forget for either club’s many ardent followers. Less than half an hour after the match had ended I remember seeing a fan already sporting a “6-0” t-shirt on the red line back to Milano Centrale. Today memorabilia commemorating the occasion can still be seen for sale outside the stadium and around the city, while fans and pundits still recall that historic night with a degree of disbelief, suggesting the result has never truly sunk in.

And what of Gianni Comandini? The two-goal hero of the derby didn’t quite lived up to expectations as one of Serie A’s most promising strikers. In June 2001 — just a month after the derby — Milan sold their number nine to Atalanta for 30 billion lire. He spent the next four seasons at the Bergamo club, with loan spells at Genoa and Ternana, before persistent injuries forced him into retirement at the age of 29. In 2006 he opened a restaurant in his hometown of Cesena, where he has been known to make appearances for Polisportiva Forza Vigne, an amateur club founded by his father, Paolo.

Comandini’s career at Milan can be summed up in that one night at San Siro: his brace against Inter constitutes his only two league goals for the club. I returned to San Siro one last time that season for Milan’s final home game against Brescia (primarily to see great Roberto Baggio in the flesh). I left Pavia, graduated, and moved back to Florence, where one summer evening my wallet was stolen as I was exiting a supermarket. I didn’t care about losing my Italian social security card, bank cards or even the sixty euros I had on me. But the plastic Champions League 2000-01 season ticket that bore my name, and that I’d carried around with me for three years, was gone forever.

In the last decade I’ve watched countless more matches from San Siro on television, both Serie A and Champions League, in bars in Florence and on my sofa at home in New York. Even today, when it’s a big game, I recall instantly the relentless sound of that chanting crowd, their beating drums reverberating through the red mist and fog, and I still can’t quite believe that I too was once there. I wonder if Comandini ever feels the same.

“Ma dammi indietro la mia seicento

i miei vent’anni ed una ragazza che tu sai

Milano scusa stavo scherzando

luci a San Siro non ne accenderanno più.”

–“Luci a San Siro”, Roberto Vecchioni

What a beautiful article ! I read it twice 🙂

molto molto bellissimo !

very nice article thanks for sharing.it turns my stomach to see what milan have become today.