The poster for Larry Crowne, the new movie starring Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts, doesn’t tell us much, besides the fact that the film stars Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts, and that they are having a pleasant time. The two actors are seen riding what appears to be a flying motor scooter, judging by the sky blue background and complete absence of gravitationally secured objects. He smiles contentedly, his eyes, twinkling behind dark shades, fixed firmly on the road (or flight path). She perches behind him, her printed silk scarf fluttering in the breeze as she releases a trademark thousand-watt grin. Neither wears a crash helmet.

Not even the movie’s title can reveal much else to prospective cinema-goers as to the purpose of this joyride through the clouds. After realizing that “Larry Crowne” was in fact the name of the movie (and not a third-billed actor) I began hoping that the name might refer to a mysterious unseen matchmaker who brings the film’s protagonists together; or maybe a clever alias exposed to devastating effect mid-way through the movie; or perhaps the leader of a menacing band of Vespa enthusiasts that engages our heroic duo in a less-than-deadly two-wheeled airborne pursuit. Imagine my disappointment to learn, with depressing predictability, that “Larry Crowne” is nothing more than the name of Tom Hanks’ character. The poster isn’t even a cute reference to Roman Holiday.

When asked about the title, Hanks, who co-wrote and directed the film, revealed Larry as the name of his real-life brother, and that “Crowne” was chosen as a last name because it “sounded cool” (probably because it had already sounded cool in The Thomas Crown Affair — twice). I can only assume Hanks was searching for a name to evoke a certain everyman, but the detail drew my attention to what may be a growing trend in Hollywood, in which movie titles — supposedly an important element in the eventual success of a cinematic release — simply defer to the lead character’s name.

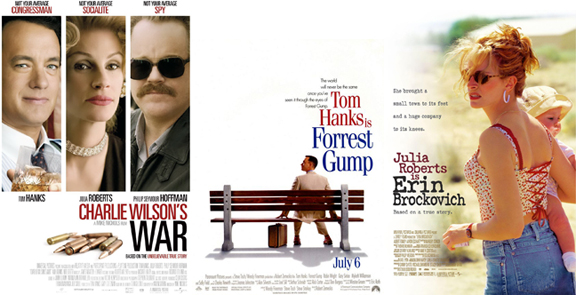

Larry Crowne is not the first movie — or even the first movie starring Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts — to include a character’s name in the title. In 2007 the pair co-starred in Charlie Wilson’s War, while each won Oscars for their respective roles as Forrest Gump (1994) and Erin Brockovich (2000). Historical tales, true stories and biopics often include the character’s name in the title for recognition purposes, since it’s that person whose life the film is about. Other comprehensible exceptions include franchises such as Indiana Jones or Harry Potter. Woody Allen’s Annie Hall (1977) told the story of a comedian’s complex relationship with a woman, the use of whose name as the title served only to accentuate his romantic fixation (“Hall” is also Diane Keaton’s real last name). A character’s name may play an integral role in plot development, as in the case of Meet Joe Black (1998) and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (2008). In both movies mystery shrouds Brad Pitt’s identity as the preposterous title character.

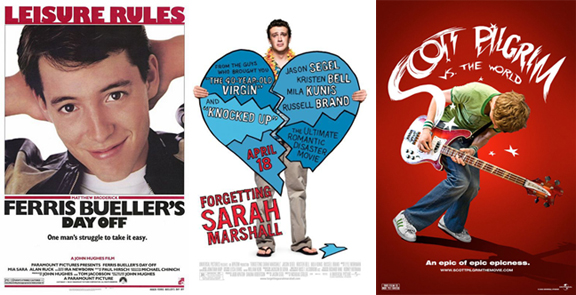

In some cases a film can gain a cult following due to the inclusion of a character’s name in the title. To a generation of movie-lovers, “Ferris Bueller” remains synonymous with adolescent tedium and smart-alec rebellion thanks to Matthew Broderick’s winning performance in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986). More recently, other films aimed at young audiences — such as Forgetting Sarah Marshall (2008) and Scott Pilgrim vs. The World (2010) — have attempted to capitalize using the same technique, with less impressive results. You could argue also that these films are either set in high schools or geared towards teens, an age where last names are important for differentiating between the dozens of other Sarahs, Scotts and, uh, Ferrises among your peers.

But when the device backfires it can make film companies look quite lazy. In 2009 two films were released with identical titles, save for their character name suffixes. The subject matter of I Love You, Beth Cooper and I Love You Philip Morris could not have been more different, but you could hardly blame audiences for not being able to recall which movie was which. Perhaps Larry Crowne‘s truest precedent is Jerry Maguire, the 1996 hit starring Tom Cruise and Renee Zellweger. It too relied on the bankability of its leads, and essentially amounted to a fairly straight romantic comedy-drama hidden beneath a tedious sub-plot about a sports agent and his ego-centric client.

Admittedly, it’s so far been a bad summer at the movies. Bad Teacher, Horrible Bosses, and Zookeeper sound like they were lumbered with their working titles when market research suggested they couldn’t be improved upon. But neither the ubiquitous poster for Larry Crowne nor its accompanying trailer has given me incentive enough to go and see it, despite the dearth of promising alternatives. A New York Times review, which described the film as a “tepid, putatively adult film which may elicit mild chuckles” suggested my instincts were correct. Maybe I’d have been more compelled if the movie had had a more interesting title (the French release translates as “It’s Never Too Late”). Instead, the public is left with no idea what the film is about, and the impression that the answer is not much. It makes the film look like a vanity project. Perhaps Tom Hanks should save himself some bother and simply call his next vehicle “Tom Hanks”.

It’s no secret that studios’ primary concern has always been star-power and box-office success. Maybe the less an audience knows about a movie the more likely they’ll pay to watch it. The fact that Larry Crowne stars two of America’s best-loved stars was enough for it to gross $15.7 million in its opening four-day weekend (although 71% of those who bought tickets were over 50). But it seems increasingly apparent now that even filmmakers themselves are becoming indifferent to their own work, a conclusion borne out by Hollywood’s current lack of imagination and fresh ideas. Imagine an alternate world where classic movies had been named for their main characters. Rick Blaine, George Bailey, Norman Bates, Benjamin Braddock, Popeye Doyle, Vito Corleone, Travis Bickle, Tony Manero and Han Solo hardly sound like Oscar-winners, but I bet you’d have little trouble recalling the movies they belong to. Hollywood should focus on creating characters worth remembering –- if they’re truly memorable we won’t forget their names.

Hilarious and so true.

Wasn’t Annie Hall used because the studio blocked Woody Allen calling it Anhedonia which was what he wanted to call it. Your point still stands but it’s worth noting.

Ben, you’re absolutely correct. I’d completely forgotten about that. United Artists thought “Anhedonia” unmarketable, and they evidently didn’t care for co-writer Marshall Brickman’s suggestion (“It Had To Be Jew”) much either.

These days the studios seem more intent than ever in marketing Allen’s pictures to mainstream audiences, despite the fact his movies have routinely alienated for thirty-odd years. His latest release was initially titled “The Bop Decameron”, but in the end they settled on the entirely bland “To Rome With Love”.