When I moved to Italy in the autumn of 2003, I was lucky enough to be offered a place to stay by an old friend of my parents, a retired English teacher named Bibi. That isn’t her real name: she’s actually called Fortunata Maria, but for reasons unknown people have always called her Bibi, so that’s what we called her too. Bibi lived in a small town called Borgo San Lorenzo, in the Mugello valley, roughly an hour north of Florence (or half an hour if you’re being driven by an Italian). I’d first met Bibi when I was eleven — my family and I had spent many summers on holiday in Italy and had stayed with her on most of those visits. Consequently I had a lot of friends in the town, and was certainly taken care of at home: Bibi’s live-in help, a Neapolitan woman named Tina, would serve me an industrial quantity of pasta twice a day, and if I didn’t eat with them it was because I’d been invited to dinner by someone else.

Despite the relatively easy life I was leading in Borgo, there was little to do there, and like most small Italian towns this one became somewhat deserted every afternoon. A typical day generally consisted of meeting friends at the bar, reading La Gazzetta dello Sport, eating a big lunch and taking a nap, before getting up and doing the same thing all over again until bedtime. As much as I genuinely enjoyed watching television dramas most nights with Bibi, it didn’t take a genius to figure out that I couldn’t stay there forever, and that for all my young person’s needs — social, cultural and professional — Florence was where it was at. I’d begun working in the city after Christmas, and the daily commute on bus and train was beginning to take its toll. Though they were little more than an hour away, the difference between Florence and Borgo was more appropriately measured in light years. By the early spring I decided that five months was about all I could take.

Through a colleague I’d been given the number of a doctor in Florence — let’s call her OC — who as luck would have it was looking to rent out a room in her apartment, which had been described to me as “gorgeous”. While sharing a house with a Florentine divorcée perhaps wasn’t my ideal living situation, it made marginally more sense than staying in a sleepy Tuscan town with a reclusive former English professor and her hyperactive cat. When my colleague began describing the spectacular view from OC’s apartment my initial hesitancy began to wane and I decided it was an opportunity I had to investigate.

OC was on the island of Capraia that afternoon when I called to introduce myself, but we arranged to meet at her apartment a week later — by which time my already overly active imagination had begun to visualize a new life in Florence, complete with all its glamorous trappings. It was a decidedly unglamorous wet spring afternoon however the day OC and I finally met. Getting off the bus in Piazza della Libertà, I walked on Via Pier Capponi for several minutes in the direction of Piazzale Donatello before successfully locating the address through the drizzle. Realizing I was half an hour early, and with no bar in sight, I was forced to take cover beneath a concrete overhang protruding from the adjacent apartment block. Opposite was a non-descript yet quite desirable row of mid-century residential buildings, of which number seventeen was arguably the largest: a big yellow construction with a pizzeria on the ground floor and a hotel next-door. The top floor apartments were graced with a long balcony running the width of the building; trying to remember what vague information I’d been provided with I suspected one of those was OC’s.

At three-thirty I made a dash across the street and buzzed: a voice responded, I pushed open a heavy metal door and entered a small lobby decked in marble and glass. The elevator had a manual wooden door with a round window like a ship’s porthole, then two narrow doors with even narrower windows. The interior of the lift was covered in a red carpet, except for a bathroom-sized mirror attached to the back wall. Arriving at the sixth floor, I pulled open the thin double doors and saw OC beaming at me through the porthole window.

The first thing I noticed were her black leather pants — more Joan Jett than medical professional — which she paired with a white boat neck long-sleeved t-shirt. Streaks of grey ran through her shoulder-length brown hair which was pulled away from her face, as though she’d just showered. I guessed her to be in her early-fifties, though her youthful manner — and wardrobe — seemed to defy her mature visage.

OC and I shook hands and entered the apartment through double wooden doors, upon one of which was a plaque engraved with “Dott.ssa” (Dottoressa). We entered a dark and roomy hall dominated by a huge wooden dresser, possibly the largest piece of furniture I’d ever seen, itself half-hidden beneath a mountain of clutter. She then led me through frosted glass doors into a spacious living room. Despite the overcast weather, light poured in through sheer curtains covering glass doors leading out to the balcony. In front of the curtains was a huge potted plant, its droopy leaves partially covering one of two comfy beige sofas. Still wearing my raincoat, I sat down in the middle of the other one, directly beneath a giant canvas depicting a barnyard scene in the moments which followed the birth of Christ. OC revealed that it was a reproduction of a Ghirlandaio fresco in the church of Santa Trinità. She said she didn’t much care for it, but since it was the work of a friend of hers she felt somewhat encumbered by it. It wasn’t the only item of interest: two giant lanterns sat in the corners of the room which had originally been used on steam engines (OC’s grandfather had worked on the railways). She then offered me a choice of coffee or limoncello. I chose coffee; a minute later she returned from the kitchen with both.

OC sat down in an armchair directly in front of me, and placed a tray between us on a matching ottoman. She then proceeded to talk. And talk. And talk — until I realized I’d finished both my drinks without barely having uttered a word. She appeared perfectly happy to skirt conventional conversation starters — who I was, where I’d come from, what I was doing in Florence and how I’d ended up in her living room. Instead she soon began to ramble almost absentmindedly about her vacation home on Capraia, right down to its shoddy plumbing. I tried listening to her with intent at first, but soon my eyes began to drift around the room, observing the hand-painted wooden panels which hung on the wall behind her, and even glimpsing the hilltop town of Fiesole through a gap in the curtains. Though bemused by OC’s complete disinterest in her potential housemate, this wasn’t enough to put me off. Her apartment was the kind of vast, sprawling, Manhattan-style pad I’d only ever seen in old Italian movies, and having got through the door I was not about to give it up. Besides, as far as I was concerned the less interest OC showed in my life the better.

I hadn’t even yet seen my room, but really I didn’t need to: one glance at the view from the kitchen sealed the deal for me. More French doors gave way to another balcony, and beyond a row of trees the city’s mighty Duomo rose up defiantly through the afternoon drizzle. I couldn’t possibly turn down this opportunity, if only to make my friends eternally jealous. We agreed on a monthly figure for rent: €350, bills included. I couldn’t believe my luck.

* * *

Less than two weeks later I arrived back at OC’s, this time with two large suitcases in tow packed with all my worldly possessions. OC welcomed me with open arms and introduced me to a friend with whom she was enjoying a post-lunch cigarette. The friend offered me something to eat — some kind of sausage and salad — which I politely accepted. She seemed more interested in me than OC had on our first meeting, who again paid me scant attention, as if twenty-something British men move into her home every week, and I got the impression I was merely a footnote upon the epic nature of her own daily concerns.

The neighborhood — Florence’s affluent Campo di Marte district just outside the centro storico — was perfect. The languages school where I taught was a short walk away, as was the football stadium, which to my delight was even visible from OC’s living room. A door off the kitchen led to my room, although I should really say quarters, since I had a hall, bedroom, bathroom and balcony (which shared the same spectacular view as the kitchen) all to myself. The room was furnished with a beautifully carved wooden bed, a large wardrobe, a small chest of drawers, an antique bookcase and a brand new IKEA desk. That night I went to bed early but was kept awake by the incessant drone of traffic emanating from Viale Matteotti, the wide tree-lined boulevard running behind the next row of buildings. I’d never lived in a town even half the size of Florence, and arriving directly from Borgo made the transition even more dramatic. From my new bed I gazed at Brunelleschi’s cupola (which appeared to loom even larger at night) as the sound of buzzing Vespas peeled up and down the street. At last, urban civilization — modern and not so modern — could be seen and heard, and the next morning I felt reborn, as if I’d just awoken from a five-month socio-cultural slumber.

OC had two beautiful children from her dissolved marriage, a girl and a boy. Though their father lived just a five-minute walk away, only one divided his time between both parents; the other (the daughter, who was older) had chosen to live permanently with her mother. Their dad lived a short walk away in Piazza d’Azeglio. I spoke to him a couple of times on the phone, and even met him once. He wasn’t particularly friendly, but then his ex-wife had suddenly taken in a foreign man half her age, so I couldn’t really blame him for being skeptical. I remember a divorce lawyer coming to the house a few times, but I never asked OC about him or why they separated. She once suggested it was because she liked to watch Stargate and he didn’t, which I supposed was as good a reason as any.

OC’s daughter was a typical Italian twelve-year old, her interests revolving mainly around horses and the British boy band Blue, yet she was sassier than most kids her age and seemed genuinely excited by this unconventional domestic set-up. Her son turned ten shortly after I moved in, and life was certainly more hectic (and louder) when he was around. Mealtimes were particularly chaotic: all three would eat at the kitchen table, and from my nearby room it seemed at times as though they were competing with the TV to see who could make the most noise.

I would often be asked to join them for dinner, an offer I readily accepted out of polite gratitude but also based on the fact that the combined din of two excitable kids and the blare of Italian primetime television made it impossible to concentrate on anything, despite the two doors which separated us. OC herself was the possessor of a booming, almost manly voice: when my Dad called the apartment and she answered the first thing he said to me was, “Who was that bloke?” Needless to say her regular breakfast phone calls to patients and colleagues soon meant I no longer required a conventional alarm clock. OC could whip up a pretty tasty pasta or roast pork, and was also fond of cooking homemade hamburgers. When the weather got warmer she regularly made gazpacho or panzanella for lunch. I enjoyed eating and watching cartoons with the kids, and in those early months we’d often engage in epic after-dinner soccer matches in the hall which would last until bedtime (or until somebody got hurt by slipping on the tiled marble floor). This was certainly preferable to spending the evening trapped with OC, for once the kids were out of sight I began to understand just what kind of person she was.

As was my initial impression, it was soon confirmed to me that OC did not excel as a conversationalist. What she did do well were monologues, and could talk quite happily for long periods without interruption. Of course, any interjection on my part was unlikely as she limited herself to discussing subjects which I knew little or nothing about: Etruscan ceramics, the commercially unsuccessful films of Gérard Depardieu, or her trip to Greece in 1971. It soon became evident that any topic in which I might offer any relevant input was strictly off-limits. When talk did turn to the everyday my opinions on food or life in Italy held absolutely no weight whatsoever by pure virtue of my being British. Conveniently, OC claimed not just her Florentine status, but thanks to her parents was also equal parts Roman and Venetian, and despite never having lived there seemed to understand everything there was to know about Naples too. With four of the country’s major cities among her areas of expertise, any comment I had to make about Italy could be dismissed in an instant. Meanwhile, OC remained completely oblivious to my own life and background.

I soon realized these were the classic traits of a very insecure person, and I began to feel some pity towards her. There was something sad about the fact that all her lengthy anecdotes recalled events which took place at least twenty years ago, as if her life had somehow stopped after having children. Sometimes her stories weren’t even first-hand: I remember one evening she recounted a lengthy tale about a friend of a friend who’d become involved in a complex romantic triangle while living in Brazil (which wasn’t as exciting as it sounds). OC’s highly elevated sense of self-importance was evident not just from her choice of subjects but also her preference for the supposedly intellectual channel Rai Tre (the third station of Italy’s state network RAI), as well as her refusal to let others speak. When a lengthy story finally drew to a close she would abruptly switch off the television, utter a one word goodnight (“Notte!”) and march out of the kitchen, like a performer exiting stage right as if to deliberately avoid the scorn of critics. Of course, there were no critics, just a speechless and weary audience of one.

After dinner OC and the kids would get ready for bed almost immediately, so by ten o’clock each night I pretty much had the run of the place. They never sat in the big living room where OC and I had had our first meeting, and rarely did I, preferring instead to work in my room, or practice my saxophone. Sometimes late at night I’d sit on the balcony with a cup of tea and admire the breathtaking panorama of floodlit Renaissance architecture. To my good fortune the other bedrooms were on the opposite side of the apartment from mine, so I could even listen to music at night without disturbing anyone. Rather than use the large double-doors, OC gave me keys to a side entrance into the kitchen, allowing me to come and go as I pleased. This arrangement worked just fine, although in the first three months I became locked inside the apartment on two separate occasions.

OC’s huge bedroom with en suite was dominated by a large bed, giant wardrobes and the strong pervading essence of Chanel. Despite the ample closet space her shoes and clothes were routinely strewn about the room like those of a messy teenager. Both kids had their own rooms and shared a bathroom, which was inevitably something of a disaster: clothes, toys and dirty towels littered the blue-tiled floor and the mirror was smeared with pre-adolescent messages scrawled in lipstick. It did not take me long to discover the kids took after their mother, at least as far as general tidiness was concerned. OC’s organizational skills left much to be desired, even for an Italian. Her office, or study, or whatever you wish to call it — personally I considered “bombsite” a more apt term — was the area worst hit. An explosion of open drawers overflowed with countless white boxes of drugs and pills, while hundreds of white paper sticky notes bearing the name of various pharmaceutical companies (the kind that doctors are given free bundles of at conferences) were scattered throughout like fallen leaves. There was a dining table in the middle of the room which was never used for dining, or anything else for that matter, as every inch of its surface was covered in the same mess.

Likewise, the kitchen table had to be cleared of bills, homework, junk mail and more of the same sticky notes each day before it could be used for eating. Most of this clutter would be unceremoniously dumped onto the nearest chair, which meant in order to sit down the same clutter in turn had to be placed onto the kitchen floor, where invariably it would remain, sometimes for several weeks. Incredibly, this untidiness had apparently extended to the interior of OC’s car — a white ’95 Honda Accord — which was identifiable by the mountains of mail and sticky notes piled upon the passenger seats. Ironically, despite all those sticky notes OC was forever without a scrap of paper to hand, so whenever she needed to jot down a phone number or an appointment — or even when helping with math homework — she would simply take a pencil and write directly onto the white kitchen table. Her later attempts to clean her scrawled notes only transformed them into unsightly grey smudges.

OC appeared equally comfortable writing on any surface of her home: upon the white-washed kitchen walls she would record her kids’ heights — and mine — at monthly intervals. I had several years (and feet) on these two Italian tykes, but unlike them I wasn’t getting any taller, so my height remained represented by a crude unwavering pencil line six feet off the ground, next to which OC scrawled my name erroneously as JAMENS. This proved another ridiculous burden I had to live with. What began as an innocent child’s mistake (my name had been entered with an unwanted “N” as we played a computer game) soon took on a life of its own, and I quickly became known as “Jamens” (pronounced Yah-mens) by the entire household. While I initially took it as a sign of affection the habit soon began to grate, particularly when OC called me by this name in front of people or when discussing more serious matters.

* * *

After six months OC and I had settled into a pretty comfortable routine, though we led completely separate lives. I ate with her and the kids less and less, for fear of being subjected to another installment of The OC Show. Instead I’d eat in a hurry before they did, often twice a day, making sure instead to always take advantage of the rare occasions when they were out. As soon as the weather warmed up, OC and the kids would spend entire weekends at their holiday villa on the island of Capraia, a two-and-a-half hour ferry ride from the Tuscan port of Livorno. Sometimes they invited me to come with them, usually at the last minute, by which time I’d usually already have social or work commitments. On the occasions when I had no weekend plans I declined the offer anyway: though the thought of relaxing on a Mediterranean island was hugely appealing, spending an intense weekend in OC’s company was considerably less so. I’d begun to value my infrequent moments of personal time more highly than anything, and those weekends home alone were more fun than I’ve ever had on any beach.

One Saturday morning in early June OC and the kids left to catch the ferry for the weekend. They wouldn’t be back until Sunday night, and so I’d decided to make the most of their absence by hosting a little party. The second they were out the door I set about getting the apartment into shape: I removed the mail and sticky notes from the kitchen table, and cleaned the kitchen floor, off of which I recovered (in addition to the usual paper products): a stale, gnawed piece of bread, assorted shapes of dried pasta and a stray pair of girl’s underwear. Having finished scrubbing every surface I had just begun preparing food when I heard a key in the front door. Panicked, I had no time to react before OC was standing in the kitchen. Turns out they’d missed the boat, literally. “Abbiamo perso la nave!” she bellowed, almost proudly, like a tipsy old sea captain bursting into the harbor tavern. Naturally, she was oblivious to how her disorganization had ruined my own weekend. (When I finally got the chance again to throw the party — almost a year later — I named the event Mamma, ho perso la nave, literally “Mommy, I missed the boat”: a direct reference to my previous hampered attempt to play host and to the movie Home Alone, which in Italy is called Mamma, ho perso l’aereo.)

You may wonder why I put up with such limited freedom (not to mention OC’s eccentricities) for so long, but for all the valid reasons for moving out there were others which kept me at Via Pier Capponi. That view for starters. Plus, I was paying less in rent than everyone else I knew in Florence and had no utilities. Best of all, in summer OC and the kids would relocate to Capraia for most of July and August, leaving me free to bask in a sun-kissed, Mastroianni-inspired, fantasy life. On Saturday mornings I’d buy La Gazzetta and La Repubblica and read them (and their glossy magazine supplements) over breakfast in Piazza Strozzi, before heading home for lunch and an afternoon tanning on the balcony. In the evenings I’d pour myself a Campari Soda while preparing dinner (a luxury in itself), after which I’d retire to the soft grandeur of the living room, where I’d listen to music, watch meaningless pre-season soccer friendlies or even indulge my passion for classic Fellini. OC had left me the keys to her bike, which meant if I wanted to meet friends for a drink I could be on the other side of the Arno in less than ten minutes. One Sunday morning I woke up early and rode into town. I circled the narrow streets and vast piazze, usually thronging with tourists but now instead deserted, as if I’d stumbled upon an abandoned film set.

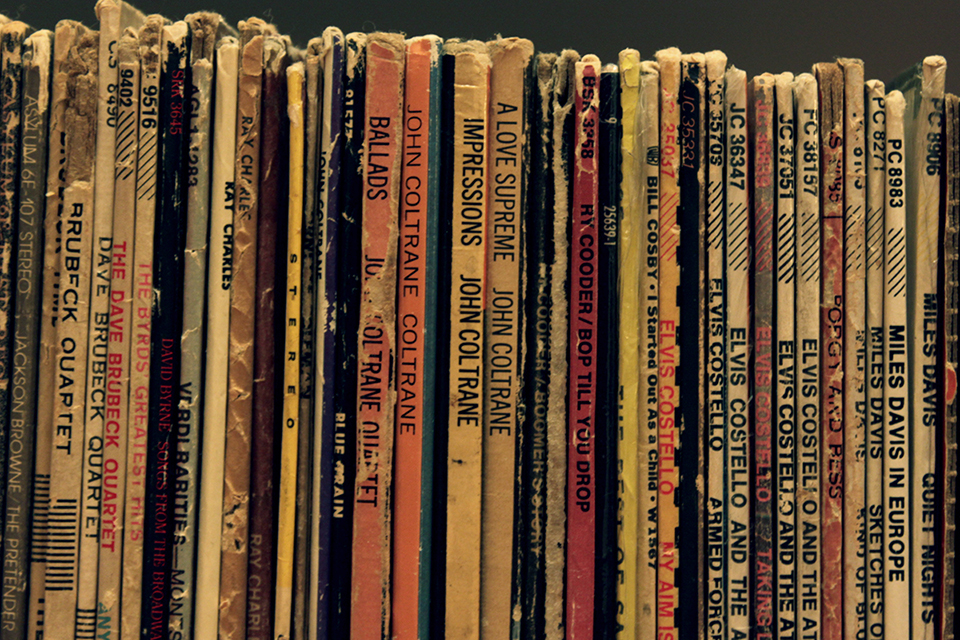

The pleasure of those two months was enough to keep me in that apartment for over two years, even though I knew my idyllic lifestyle was destined to end as soon as OC & Co. returned to Florence. In their extended absence the apartment had become all mine, a spotless paradise cultivated in my own image. I even transferred my stereo into the living room, where I’d lounge and plunder through my collection of classic albums. Sadly, this perpetual bliss was punctured the second OC’s front door key twisted the lock. Immediately, it was as if they’d never left: bags were thrown on the floor, clothes were dumped on the backs of chairs and clutter — keys, mail, toys, whatever it may be — were laid to rest on any available surface. I retired to my room and began calling up my friends in search of an escape.

Having become so accustomed to having the place to myself, when OC and the kids returned I’d look for any opportunity to stay out of the house. When friends suggested meeting for dinner or a drink I never hesitated; when no such offer was forthcoming I’d be content to roam the streets for as long as I could, until, defeated by cold or hunger or both, I’d reluctantly return home. If I could wait until ten I’d generally be guaranteed to avoid running into OC, which in part made me quite willing to work long hours at the languages school where I taught. Sometimes I’d go out for a drink or a pizza with students or colleagues, other times I’d go directly back to a now silent apartment. If OC did happen to still be up past ten, I’d often walk into the kitchen to find her watching TV, at which point she’d thrust a glass of limoncello into my hand. “Chi non beve in compagnia o è un ladro o una spia,” she’d say to me, which literally translates as, “He who doesn’t drink in others’ company is either a thief or a spy.”

Before I could respond, or escape, OC would launch into one of her famous monologues, perhaps a predictable anti-Berlusconi tirade or simply a depressing review of contemporary Italian society’s general malaise. Let’s just say OC didn’t do small-talk. As a self-proclaimed Florentine, she was the first to criticize the city for its problems and shortcomings, but also quick to defend it. If I’d been to a restaurant for dinner, rather than ask me where I’d eaten or how the meal was she’d simply scoff, “Ha! Us Florentines would never dream of eating out in the centre of Florence!” Once she asked me completely out of the blue if I’d ever been to Venice. I had, though not in about fifteen years, but thinking fast I answered, “Yes, many times.” I could actually see the disappointment on OC’s face, as this meant she had to limit her speech to just five minutes, and the hour-long lecture to which I would otherwise have surely been subjected would have to wait for another time, or another unsuspecting victim.

Any pity for OC this scene may invoke should be disregarded immediately. I did pity her, but her situation was caused purely and solely by her complete social ineptitude. The few friends of hers I did meet were very nice, and always showed a much greater interest in me than she ever did. They never failed to compliment me on my Italian, something OC herself never once acknowledged. Perhaps predictably for someone with such vast insecurities, she clearly began to resent me for having any kind of social life of my own, and on the rare occasions when my friends and OC did cross paths she was usually rude or at the very least inappropriate. One stormy Sunday night a colleague, SM, an at times painfully polite British woman and a dear friend, came over to pick me up on the way to the movies. OC was ironing in the kitchen when I introduced the two women to each other. “Have you come to prepare lessons together?” she sniggered between drags on a cigarette, before letting out a nicotine-induced chuckle. SM, clearly taken aback, seemed forced to defend herself. “Actually, we’re just going to the cinema.” Sadly OC’s pathetic comment was pretty typical, which is why I avoided inviting people over unless I could guarantee that she wasn’t going to be around.

I’d been at Via Pier Capponi for little over a year when I became involved with JP, an American woman whom I’d originally met in the spring of the year before, just a couple of weeks after moving to Florence. JP was visiting Florence for the summer, and spent several nights at the apartment, though we usually only returned home after midnight. One Saturday afternoon we ran into OC as we were leaving the house, just as she and the kids were sitting down to lunch. The kids waved ciao and OC herself seemed perfectly at ease with the fact that a girl had spent the night in my room. I was twenty-six after all — could she really be surprised?

The summer rolled on and JP and I spent many more nights in the apartment together, including whole weekends while OC was in Capraia. Officially, JP was staying in the apartment of a mutual friend, who was also out of town, so other nights we’d stay at her place. JP left Florence at the end of June, by which time OC and the kids had moved to Capraia for July and August. When they eventually returned from the island, almost two months later, OC took me aside as I boiled water for a cup of tea. “James, don’t bring people into the house,” she told me coldly. “It’s a problem for the kids. And a problem for my ex-husband.” It struck me as extremely inappropriate that her ex-husband might be weighing in on my private life, and I knew for a fact that the kids had no problem with it (they’d even asked me excitedly about it). Of course, OC had neglected to mention the real issue, which was that it was a big problem for her. What really irked me was her use of the word gente (“non portare gente in casa” was what she’d said) as if I was picking people up off the street each night. She’d never mentioned anything about me having people over, but I don’t know what else she expected. Maybe it had never occurred to her. At that point I vowed (to myself at least) never to bring anyone else into the apartment, and to begin actively seeking alternative accommodation.

* * *

By now my motives for moving out were beginning to outweigh the reasons to stay. Though the apartment belonged to her, OC had never once attempted to adjust her lifestyle to suit the fact that I was now also living there. She showed little or no respect for my needs, and it seemed both unfair and ridiculous that I shouldn’t be able to indulge in normal social activities. And as spectacular as that view still was, it certainly wasn’t enough to make me put up with everything else. I’d also now come to the realization that OC was not just untidy and disorganized, but actually dirty. Mystifyingly, she seemed incapable of using an ashtray, and would routinely flick ash into the kitchen sink, where it would fall onto the stack of dirty dishes which remained from lunch. Once, as I attempted to clean the living room, I came across an upturned ashtray under a coffee table, its grey, powdery contents now embedded into the rug. On one unpleasant occasion I even found a partially used cigarette in my own bathroom: evidently OC had been smoking while doing laundry (my bathroom also housed the apartment’s only washing machine), and had simply extinguished it in the nearest receptacle.

Meanwhile, OC’s now teenage daughter had also become less pleasant to be around. I’d somehow been oblivious to her transformation from pony-loving child into sulky adolescent, which she’d managed to complete in the space of just a few weeks. Only months earlier I was being dragged into town by her and her friends to go shopping or helping her choose an outfit for a party at her behest. Now I barely saw her, and only reluctantly would she acknowledge me when I did. I put this down to teenagerdom but it was clear I was no longer a novelty in the household. Even OC’s generosity toward me had waned. When my wallet had been stolen a few months after I moved in she’d lent me the €60 I’d lost, now she barely gave me the time of day.

Whether she knew it or not, OC was headed fast for another divorce, this time without even getting married. By the spring I couldn’t wait to move out, and nothing about her behavior looked likely to make me change my mind. In March I left to visit JP in New York, just days after learning that my grandmother had been hospitalized having suffered a severe stroke. When I returned to Florence there was a message from my Dad telling me she’d died. “Yeah, a patient of mine died the other day,” was OC’s immediate and thoughtless response, which only demonstrated that she was even more self-absorbed than I’d originally thought.

Immediately I began consulting friends about alternative living situations and scouring the hundreds of apartment ads which litter Florence’s streets and lampposts. That summer’s World Cup gave me the perfect excuse to be out all night watching football and was a welcome distraction from apartment hunting. One weekend in June I took the train up to Milan to visit a friend on Lago Maggiore. I had no idea of the surprise which awaited me on my return.

I had an early start on Monday and was in the middle of making breakfast when OC breezed into the kitchen, still wearing her dressing gown and enjoying an early cigarette. “Buongiorno, Jamens,” she said. We never ran into each other in the mornings so I should have perhaps known this time would be memorable.

“I’ve got some news for you,” she announced, as I stood eating my cereal. “We’re moving house!” I spluttered milk onto my tie. I was genuinely shocked, and had so many questions, mostly of the what/when/where variety. OC helpfully filled me in and told me the address. “Number eleven, like the bus. We move at the end of the month.” I assumed this had all happened suddenly, but in actual fact it turned out OC had been negotiating the sale of the apartment for some time.

“I’m so glad it’s all over,” she confessed. “Because the whole situation has caused me a lot of stress.” Naturally, OC failed to acknowledge the stress that had suddenly been placed upon me, as I now found myself with less than two weeks to find a new place to live. To my astonishment, it evidently had not occurred to her that I might see this as a healthy opportunity to move out.

“Obviously, you can come with us,” she explained. “The new place is smaller, but you can share with one of the kids.” Her suggestion was so preposterous as to literally leave me speechless. My current living situation was already less than ideal; I definitely wasn’t about to make it worse by sharing a room with a twelve-year-old. Instead, I declined OC’s offer, explaining how I wish I’d had more time to figure out just what I was going to do.

That afternoon I met my friend KO for a coffee, who generously suggested I move in with her. She was about to leave for Barcelona for a month, so it seemed like a handy stop-gap solution. I began packing up my possessions into large boxes, and the night before she left moved the first of them into her studio. The new apartment was only a ten-minute walk away but it took me the best part of four days to transfer everything. Most of this work had to be carried out either late at night or early in the morning; it was the last days of June, and by mid-morning simply too hot to be walking under the beating sun, let alone with luggage in tow. On the fourth day, a Sunday morning, I ran into OC in the kitchen as I lugged the final few boxes to my new lodging. Still in her robe, cigarette in hand, she seemed confused.

“Wait,” she said, apparently struggling to grasp what was happening. “Are you moving everything on foot?” With a wine box full of paperbacks in my arms and a giant Benetton duffle bag over my shoulder I could only muster a shrugged “Yeah”. Exhausted, I slumped my cargo onto the kitchen floor, expecting her to offer to help me take the rest of my stuff in her car, which was parked downstairs. It would have been great had she suggested it earlier but I wasn’t about to refuse. At that point she continued. “Well, think of the money you’ve saved instead of going to the gym.” OC turned on her heel and exited the kitchen, stage right. It was the last conversation we ever had. I hauled the remaining bags and boxes into the elevator and left Via Pier Capponi for the final time.

The next two months were spent living in a tiny studio which could barely contain all my possessions, and when KO returned from Spain we were forced to share everything, including a bed. My attempts to find a place of my own proving frustrating, in the end we both wound up moving into a new apartment together, by miraculous convenience located directly upstairs. It was a beautiful, four-bedroom property, and the size of the place meant we had to find two extra roommates. By extraordinary serendipity the first person to answer our ad was HG, an Italian literature student who soon became my girlfriend. My new landlady, a highly strung and heavily pregnant woman clad head-to-toe in checkered Burberry, was, in many ways, the exact reverse of OC, yet together with our new roommates, still proved capable of causing me bundles of unwanted stress (but that’s another story). I finally felt my luck was changing: I was enjoying my new life and the undoubted freedom it brought me. Meantime still I had heard nothing from OC.

The months went by, then one early summer evening I was on my way to a Fiorentina game when not far from the stadium I noticed a white Honda, not unlike OC’s, caught in the matchday traffic. The car passed me as I prepared to cross the street, but the low sun’s glare gave me no chance of identifying it as hers or not. When I’d reached the other side I turned and saw a dog stick its brown head out of the backseat window, before the car itself disappeared quickly around the corner and out of view. Knowing OC didn’t have a dog, I could only assume it had been somebody else.

The following afternoon, I was sitting reading the paper when my phone beeped. It was a text message from OC! Turns out the white Honda had belonged to her after all:

“Evitare il saluto è un gesto scortese privo di buoni motivi. Buona fortuna.”

“Avoiding a greeting is an impolite gesture without motive. Good luck.”

(It should be pointed out that to genuinely wish someone luck in Italy one says “In bocca al lupo” or “into the mouth of the wolf”, to which one always should reply “Crepi” or “Death to the wolf”; OC’s use of the literal term “good luck” was clearly meant in a less than positive, dismissive sense.)

Almost a year had passed since I’d moved out and this was the first time I’d heard from her. Not a phone call to see where I’d moved, not an invite to their new place for dinner, not even an SMS to check I was still alive — until now. I debated over replying for several minutes; on the one hand it was such a resentful message I didn’t want to give weight to it, but at the same time I didn’t want her to go through life thinking I was the one with the problem. So I wrote back explaining that I hadn’t seen her and if I had I’d have naturally said hello. Perhaps unsurprisingly, I never heard from her again.

HG and I moved out in June, and it wasn’t many months later that we found ourselves in New York. Sometimes, when I’m watching Fiorentina on cable television, or even if I hear an Italian voice on the street, my mind drifts back to Florence and begins to reminisce. I wonder what OC and the kids are up to now. I think of her blaring voice, the cigarettes and those endless monologues. I remember scorching, Campari-drenched afternoons on the balcony, and long winter nights with just Chet Baker and Amaro Lucano for company. You might call such recollections of Via Pier Capponi affectionate, nostalgic even. And maybe that’s what they are. But the only thing I ever really miss is that view.