The World Cup wouldn’t be the World Cup without its controversial episodes, and in the last week this tournament’s been full of them. Thanks to the blogtacular age we live in, such events can propel fans around the globe to express their unsolicited points of view with extra vociferousness. What’s most remarkable this year however, is that the incident that’s got people talking the most wasn’t all that controversial. But it was certainly dramatic. With the quarter-final between Ghana and Uruguay poised at 1-1 in extra-time, an entertaining and closely fought match was just seconds away from a penalty shoot-out when Uruguayan forward Luis Suarez cleared Dominic Adiyiah’s goal-bound header off the line with his fists, thus illegally preventing an almost certain winning goal. Portuguese referee Olegário Benquerença had no hesitation in showing Suarez a red card and awarding a penalty to Ghana, which Asamoah Gyan crashed against the crossbar with the last kick of the game. Uruguay won the subsequent penalty shoot-out 4-2, and advanced to the semi-finals for the first time since 1970.

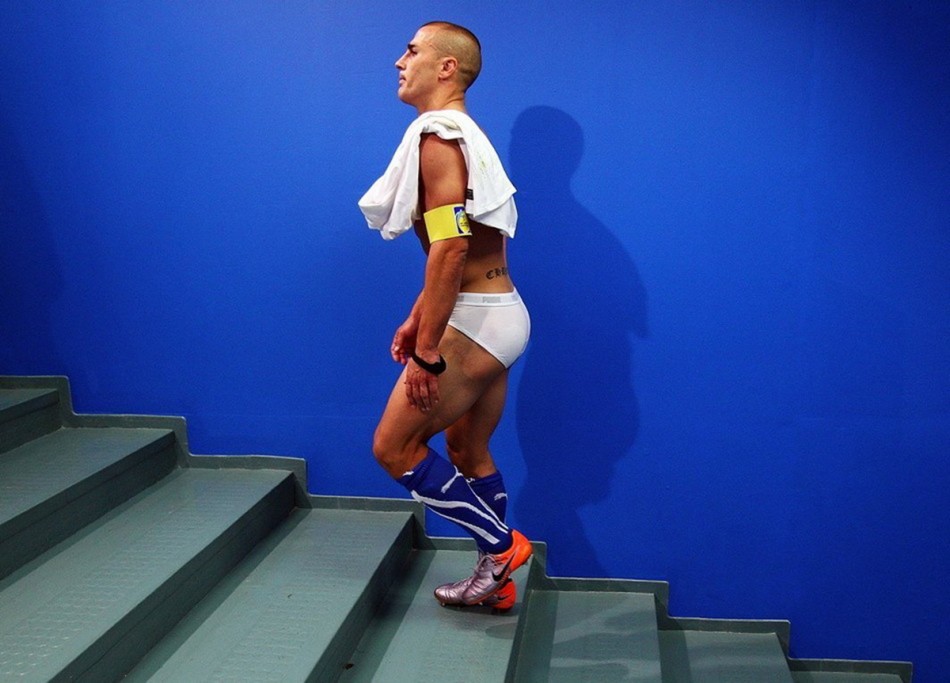

Perhaps Suarez did little to ingratiate himself to Ghanaian fans when, moments after receiving his marching orders, he interrupted his journey back to the dressing room to celebrate Gyan’s penalty miss while halfway down the tunnel. After the game he perhaps overstepped the boundaries of good taste in comparing his crime to the most famous handball of all. “The Hand of God now belongs to me,” he joked, a banal reference to Diego Maradona’s fisted goal against England in 1986 which is likely to garner more headlines in England than in Ghana.

But while Suarez will, as expected, sit out Uruguay’s semi-final against the Dutch on Tuesday, there are those that feel that this particular sporting injustice warrants further investigation, starting with a lengthier suspension than just the compulsory one-match ban. Those outraged by the incident say Suarez — and by extension, Uruguay as a team — need to be suitably punished. What they fail to remember is that the appropriate punishment was dealt immediately, in the form of a red card for Suarez and a penalty for Ghana. After that it was up to the Ghanaian player to score; it’s not Uruguay’s fault that he didn’t. Any player who wouldn’t have done the same thing as Suarez surely shouldn’t be playing professional football, an attitude shared it seems by anyone who has ever been involved in the game, judging by the solidarity shown to the Uruguayan by television’s legion of football punditry.

In a World Cup which saw two staggering errors by officials the last round, this latest controversy — unlike those involving Frank Lampard and Carlos Tevez last weekend — at least cannot be pinned on the referee. The incident inevitably drew comparisons with Thierry Henry’s handball against the Republic of Ireland in a World Cup play-off back in December, in which the French forward controlled the ball with his arm before laying on a pass for William Gallas to score the winning goal. But Henry’s crime was far worse than Suarez’s, for two reasons. Firstly, the circumstances were not so extreme as to cause Henry to act instinctively: it was not the final minute of the match, and had Henry let the ball fall out of play he would have only conceded a goal-kick. Secondly, and far more importantly, is the fact that Henry’s foul was not spotted by the referee.

In basketball, towards the end of every close game (the final two minutes) the trailing team commits tactical fouls in the hope that the opposition will miss the free throw, allowing them to retain possession as quickly as possible. What we saw in Johannesburg was essentially the same tactic applied to football. It doesn’t happen as often in football simply because the consequences (penalty, red card) are far greater. Had Suarez committed the handball earlier in the match it would have been riskier for the team, but since it was in the dying moments he decided it was preferable to Uruguay’s elimination — a practical certainty had he let the ball fly past him and into the net. A friend of mine pointed out that this incident was unusual because Suarez had no incentive not to commit the foul (besides sacrificing his own personal involvement in a possible penalty shoot-out and the rest of the tournament) due to it occurring in the last minute of extra-time. But how does a referee determine at what point there would have been an incentive to concede the goal? Those who follow football are always complaining about a lack of consistency among officials; it would be highly hypocritical, as well as ludicrous, to expect a referee to apply different measures based on the match’s circumstances or how many minutes are left on the clock.

Many have gone so far as to brand Suarez a cheat. But breaking the rules and cheating are not the same thing. To cheat is to break the rules while seeking to avoid punishment. Of course, if a player breaks the rules he should be punished accordingly. But how have these critics managed to quantify the morality of a foul? By their rationale, should a defender not bring down a forward if he’s through on goal because it would be immoral? A foul is a foul: a trip in midfield is punished with a free-kick for the opposition; a handball on the goal-line is punished with red card and a penalty. What’s the difference?

Moreover, Suarez was not trying to cheat. He knew what he was doing and what punishment would be forthcoming (despite his “Who me?” gesture towards the referee as the red card was brandished). To describe Suarez’s actions as “immoral” is to suggest he shouldn’t have committed the foul in the first place. This, to me, is a moral misinterpretation of the game. When you begin to imply that certain fouls should not be committed in the name of sportsmanship, the whole sport unravels and is rendered pointless. Players have no moral obligation to FIFA, God, or anyone else – that’s why there is a referee. There is nothing whatsoever immoral about a handball: it was a foul, and on this occasion under extremely dramatic circumstances, but the referee saw it and made the correct decisions. Had he missed the incident, then there would have been suitable cause for outrage.

By extraordinary coincidence, Ghana were involved in an almost identical incident earlier in the tournament, when Australia’s Harry Kewell used his arm to stop a shot on the goal-line for which he too was rightly sent off. Had Gyan tucked his penalty away against Uruguay as he had against the Socceroos, I doubt many people would have spent the weekend criticising the South Americans. It’s also important to consider how reaction to this incident might have differed had the situation been reversed. I think much of the outrage stems from tired Anglo-centric footballing stereotypes: the “happy-go-lucky” Africans thwarted by the “cynical, cheating” South Americans. This reveals a tiresome double-standard among football followers, and shows exactly to what extent most people who saw an injustice in Friday night’s game allowed their opinions to be swayed by context. Several neutral fans I’ve spoken to about the handball incident strongly disagree with my take on it and have all put forward arguments as to why. But they are ultimately united in their inability to assert real culpability, each independently and vaguely describing Suarez’s actions as “not right.” So if you can’t blame the player, and you can’t blame the referee, perhaps on this occasion there is no-one to blame.